On January 29, MPs from the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) clustered around 46-year-old party leader Alice Weidel in parliament taking selfies. Weidel, dressed in a white rollneck and navy blazer, gave a reticent but pleased-looking smile at the camera.

Moments earlier, AfD had made history. For the first time since entering the federal parliament in 2017, its votes had influenced national policy.

The motion to restrict immigration was nonbinding. What mattered was that the centre-right opposition Christian Democratic Union (CDU), which brought it forward, and the libertarian Free Democratic Party (FDP), who supported it, relied on additional AfD votes to pass it.

In so doing, CDU leader Friedrich Merz abolished a post-war consensus among mainstream parties to ostracise the extreme and far right.

“Merz was avoiding eye contact, the [ruling] Social Democratic Party (SDP) was furious, the AfD was over the moon, standing on chairs, embracing each other,” Jens Bastian, an economist with the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, told Al Jazeera.

“It was as if the AfD had scored the goal to win the championship: ‘We’ve provided a majority. We’ve become acceptable,’” he said.

A week before the vote, a mentally unwell Afghan man had attacked a group of children with a knife at a park in Aschaffenburg near the western city of Frankfurt. He killed a two-year-old boy and a 41-year-old man who tried to protect him.

Weeks earlier, a Saudi-born man had rammed a car into a crowd of Christmas shoppers, killing six people in the eastern city of Magdeburg.

The attacks sparked public outrage and calls for tougher migration measures.

Merz, who is leading in the polls before Sunday’s federal elections and is Germany’s likely next chancellor, “felt he had to do something visibly different”, retired diplomat Christian Schlaga told Al Jazeera, referring to the January 29 vote.

“I believe it is wrong,” former CDU Chancellor Angela Merkel said on her website.

Two days after the motion was passed, Merz brought a legally binding bill to the Bundestag to toughen border controls, restrict migrants’ rights to bring family members to Germany and allow federal police to issue their own arrest warrants. The measure failed.

Stung by criticism that they were making common cause with the far right, a dozen CDU MPs refused to back their party leader a second time.

Weidel was incensed. “Merz doesn’t have what it takes to be chancellor,” she told reporters. “The conservatives aren’t united.”

Last month’s collaboration at the federal level didn’t seem to affect the CDU’s standing in the polls, suggesting not all Germans are as affronted by the inclusion of the AfD in decision-making as the Berlin political elite.

Like Chancellor Olaf Scholz of the SPD, Merz has promised he will never enter into a coalition with the AfD and Weidel.

But he seems to be testing the waters of ad hoc collaboration. This is partly born of necessity. Merz may need AfD votes in the Bundestag in future, especially to clamp down on migration.

As Germans prepare to vote, the AfD, which is polling at 21 percent, is on track to become the second largest party in the next Bundestag after the CDU. Weidel is the face of the anti-immigrant AfD and their candidate for chancellor. So who is she, and how is she shaping her party?

Weidel attends a commemoration after the Christmas market attack in Magdeburg on December 23, 2024 [Ralf Hirschberger/AFP]

Weidel attends a commemoration after the Christmas market attack in Magdeburg on December 23, 2024 [Ralf Hirschberger/AFP]Rising through the ranks

Weidel, who grew up in a middle-class family in a town in northwest Germany, came to politics after a career in finance. She studied economics as an undergraduate, has a doctorate after writing her thesis on China’s pension system, and worked as an analyst for Goldman Sachs and Allianz Global Investors in Frankfurt. The Konrad Adenauer Foundation, which is affiliated with the CDU, financed her doctoral thesis, which may suggest she started out as a moderate conservative. Before joining the AfD, she had her own consulting firm. She is married to a Sri Lankan-born woman with whom she has two sons and divides her time between Switzerland and Germany.

Weidel joined the AfD in late 2013, the year it was founded by a group of eurosceptic academics, and quickly rose through its ranks. It was formed in opposition to bailouts for countries affected by the eurozone debt crisis. The AfD argued for what it said was reclaiming Germany’s sovereignty from the European Union and attracted antiglobalisation reactionaries, nativists and antisystem supporters of various kinds, including neo-Nazis. Weidel was drawn to the AfD before it moved rightwards to target immigration over her opposition to the bailouts.

By 2015, Weidel was on the AfD’s federal executive committee, and after the party entered the Bundestag in 2017 – taking 12.6 percent of the federal vote to become the third largest party – she became rapporteur of its parliamentary bloc. Both in the 2017 and 2021 elections, she was AfD’s co-leader with Tino Chrupalla, an eastern German politician.

Meanwhile, after Greece and other struggling eurozone members had been bailed out and the euro secured, foreign policy choices under Merkel to serve Germany’s economy, the largest in Europe, unravelled.

In 2020, a German-designed trade agreement facilitating exports to China was shelved under pressure from the United States. The COVID-19 pandemic in the same year doused consumption and shuttered factories.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 interrupted imports of cheap Russian gas to energy-intensive German industries when unknown actors sabotaged the Nord Stream gas pipelines under the Baltic Sea.

These shocks raised German energy costs. The resulting inflation undermined Scholz’s coalition government and benefitted the AfD.

“Exports to China, cheap imports of energy from Russia – that was the economic model that defined [post-communist German] reunification and the Merkel era. That model is gone, and it really was the hallmark of a successful Germany,” said Catherine Fieschi, a fellow at the European University Institute in Paris who specialises in populist politics.

Weidel is elected as the AfD’s candidate for chancellor on January 11, 2025 [Matthias Rietschel/Reuters]

Weidel is elected as the AfD’s candidate for chancellor on January 11, 2025 [Matthias Rietschel/Reuters]Strategy and staying power

Weidel has blamed globalisation for Germany’s troubles and tapped into voter discontent.

“We have had … incredible growth from 2010 until 2021. Who wants to give that up again?” Schlaga asked, describing how many voters feel.

Fieschi described Weidel as “ambitious” and “ready to mutate and do whatever it takes and find the right conveyor belt to really crack the system” of German mainstream party politics.

“Weidel basically has decided the way to get to [power] is to go via a formerly intellectual party, turn it into a populist party, hitch it to the east and then go mainstream from there,” said Fieschi, who sees her as an able strategist.

She has called for tighter restrictions on immigration, blamed Europe’s transition to green energy for costing German jobs and supports a return to fossil fuels.

Weidel focused much of her campaigning in the former East Germany.

The AfD has been particularly popular across the east, which has remained poorer than western Germany after reunification and is a natural “reservoir of votes of dissent”, Fieschi said.

But it is also, Fieschi argued, more tolerant of far-right rhetoric than the former West Germany.

“For her supporters in the east, she really doesn’t have to try that hard because in the East German imagination, … Nazism happened in West Germany,” Fieschi said.

“That is pretty strategic thinking, and the strategy totally overtakes the ideas. The ideas are whatever it takes at any given moment in time,” she said.

As the AfD’s message and identity have expanded from its original focus on the euro to addressing migration; energy; the parlous state of Germany’s armed forces, for which Weidel supports bringing back conscription; and the European project as a whole, Weidel has had the most staying power.

“The party has consumed a lot of founding members,” Bastian said.

In 2022, AfD co-chairman Jorg Meuthen resigned after what he described as a power struggle against the party’s hardliners, who he said included Weidel. In May, Maximilian Krah, the lead candidate on AfD’s European Parliament ticket, was pressured to step down from the party’s federal executive committee after telling an interviewer not all Nazi SS paramilitary members were criminals. Meanwhile, Weidel has embraced members like Bjorn Hocke, who has twice been found guilty of using a Nazi slogan.

Outwardly, Weidel comports herself professionally, wearing suits and sporting a handkerchief in her breast pocket. She plays up her professional experience and competence.

“She says, ‘Yes, I talk to [Chinese President] Xi Jinping in Mandarin. I read Chinese policy documents in the original. I understand in which direction China is going, I’ve worked there.’ That’s about competence but also foreign policy the other [party leaders] have no answer to,” Bastian said.

She’s also a savvy communicator, reaching young voters on TikTok and X.

One of Weidel’s recent videos shows her hiking in a snow-covered, forested landscape, presenting a wholesome image as she recites the chancellor’s oath. “I swear that I will dedicate my strength to the wellbeing of the German people, to promote their welfare, protect them from harm,” she says in her voiceover,.

“She has become the face of AfD. Two-thirds of Germans would not be able to name the other leader,” Bastian said, referring to Chrupalla.

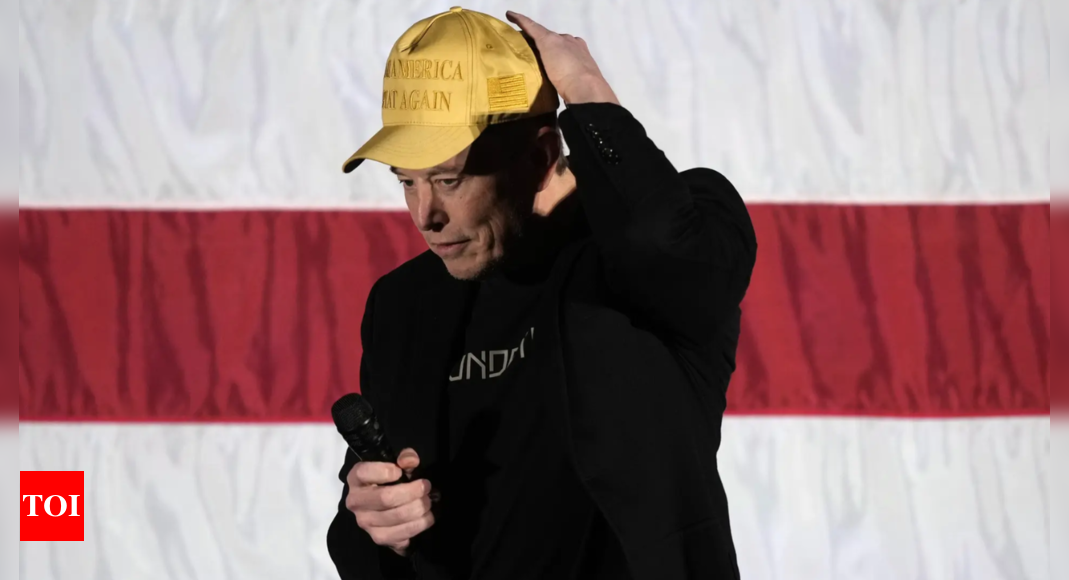

Meanwhile, in an interview with billionaire Elon Musk on X last month, Weidel as the face of the AfD performed a verbal and ideological somersault. The far-right party has tried to distance itself from Nazism, and Weidel’s historical revisionism recast Nazis as “socialists”.

“The biggest success [of the left] after that terrible era in our history was to label Adolf Hitler as right and conservative. He was exactly the opposite. … He was a communist, socialist guy,” Weidel told Musk.

“We are exactly the opposite. We are a libertarian, conservative party. We are wrongly framed the entire time, and we would like to free the people.”

Weidel prepares for a live X interview with Musk in her office in Berlin on January 9, 2025 [Kay Nietfeld/Pool via AP Photo]

Weidel prepares for a live X interview with Musk in her office in Berlin on January 9, 2025 [Kay Nietfeld/Pool via AP Photo]‘Saying things’ other parties aren’t

Weidel’s gift seems to be channelling dissent and, by voicing it, allowing others to express it.

“Germans need someone to express their anger” over falling living standards, Fieschi said.

Weidel’s positions, which break with political orthodoxy, also implicitly tell German voters it’s not reprehensible to speak their minds, even if what they have to say is negative or politically incorrect.

“Immigration was difficult to touch for parties. … She’s saying things that other political parties are not saying on an issue that is more important to more voters than other parties have been willing to [admit],” Christina Xydias, a political scientist at Bucknell University in Pennsylvania who’s written a book on German female politicians, told Al Jazeera.

At a party rally in Riesa in eastern Germany last month, Weidel spoke in favour of mass deportations, rehabilitating a far-right term that denotes stripping foreign-born, naturalised Germans of citizenship and sending them back to their countries of origin.

“I have to tell you quite honestly, if it’s called remigration, then it’s called remigration,” she thundered.

“The whole audience got up,” Bastian said, describing the audience’s exhilaration. “Remigration. The term went mainstream.”

“There are suggestions that the AfD, if they really want to make a difference, have to go a bit more mainstream, tone down the rough edges,” he said.

“I’m not convinced. The AfD are precisely gaining because they’re not doing it. They’re seen as the original, as the authentic, as the ones who are saying it the way it should be said.”

Weidel “has helped give the AfD the image of competence,” Bastian said. “Three years ago, you wouldn’t have talked like that about the AfD.”

7 hours ago

2

7 hours ago

2