Youth Music

Youth Music

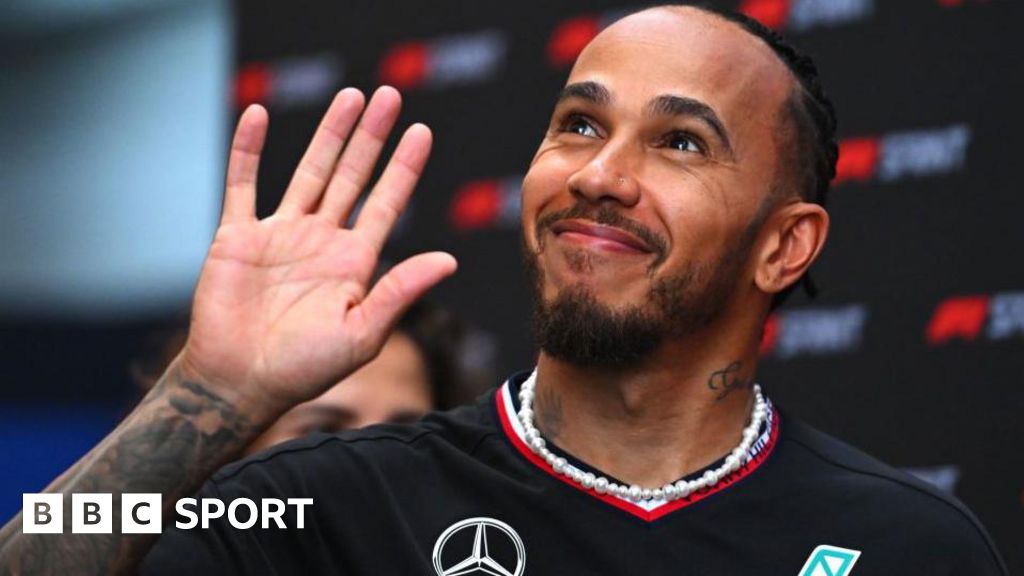

Richard Carter won the Rising Star award at the Youth Music Awards this month

Whether it's tapping a keyboard, playing the recorder or mastering the maracas, lots of us have probably had similar experiences of music lessons in school.

But some artists have been telling the BBC they want to see a greater focus on black British music and its rich history in schools.

"It was the black British artists of this country that truly drove me," says Jordan Stephens, one half of pop/hip-hop duo Rizzle Kicks.

The Department for Education in England says it's carrying out a review due to be published next year, which will look at how a new curriculum could reflect "the issues and diversities of our society" across the rest of the UK.

Previously, children's author Malorie Blackman has called for schools to teach black history all year round, while in 2022 Wales became the first UK nation to mandate black history in schools, which includes a National Plan for Music Education.

"I didn't find any of my identity through what I learned in school at that time," Jordan says at the Youth Music Awards.

"I was fortunate enough to have really inspiring people around me encouraging me to search for knowledge outside of school."

Richard Carter, who won the Rising Star award, agrees with the need for a curriculum update, and says it would have had an impact on him.

"I think I’d be more in touch with the black British music that we have now.

"The way I found it was just through going online, word of mouth, but it would be cool if that stuff was taught as opposed to just teaching me about Mozart and Bach.

"Chuck in Skepta, chuck in Jme – you need to learn about grime because you need to understand the roots. If you don’t know the roots, you’re not going to grow."

Youth Music

Youth Music

Jordan Stephens from Rizzle Kicks says nothing he learned at school helped him discover his identity as an artist

But while the Jordan says the curriculum needs a refresh, he hesitates over whether music should be split by the colour of an artist's skin.

"I would argue that it doesn’t even need to be categorised as 'black British music'," he says.

"There are British artists that happen to be black that have contributed an infinite amount to our culture and our creation."

'Seeing your idols is where everything starts'

Since 1996, the Mobo (Music of Black Origin) awards have been handed out and dedicated to celebrating black music and culture.

Producer Benjamin Turner feels "there isn’t actually any good reason for black music to not be" taught in schools.

Benjamin often works in schools and currently manages The Spit Game - a London-based collective of young artists exploring music, film and fashion.

"It’s just around the understanding of the teachers and exam boards which is holding it back," he thinks.

In 2020, University College London found almost half of schools in England and Wales have no ethnic minority teachers at all, even in diverse areas with a lot of black and Asian pupils.

"When I was in the classroom, it was really being led by the cultures and interests of the young people," says Benjamin.

"Inevitably because black British music’s such a big part of culture today – especially teaching in London – it just became a part of what we were doing in the classroom."

He feels adding it to the curriculum would serve to inspire the next generation of talent as well as lighting a path to a future career.

"As soon as it’s brought into the classroom then the capacity for them to reach the level they want, to explore the industry they’re interested in, suddenly becomes possible for them," he says.

"When you can combine passion and career potential in such a meaningful way, that’s what they need to be looking at."

Benjamin Turner (centre) manages The Spit Game in London and thinks teachers need to be better educated on black music

An early exposure to black British music can also impact understanding of sound and confidence, according to DJ Vanessa Maria.

"Especially understanding the roots of electronic dance music being black," she says.

"I didn’t know that when I was at that age.

"I thought dance music wasn’t for me, I didn’t know it was made by people who look like me, that’s for sure."

Vanessa was nominated for the Rising Star award and thinks more education is also important for building emerging talent's belief.

"From representation, to confidence, to young people, young black people themselves understanding their heritage... it’s absolutely imperative," she says.

"Imagine what amazing music is [going to emerge] from people being exposed to different genres at such a young age.

"Seeing their idols, inspirational music leaders and musicians… that’s where everything starts."

Vanessa Maria (right) says learning more about black music in school would have helped her understand herself

Up-and-coming singer Maddie Juggins feels there is scope for more music to be taught in schools.

"Black people are as talented as white people. That’s really important - the music is so diverse and incredible," she says at 1Xtra's Introducing Live, an event offering opportunities to young artists.

She thinks there has been an unfair negative stereotype about black culture.

"I think it should be in more studios, TV shows, everywhere. It should be included - we’re all equal at the end of the day.

"The music we hear, like Dave, Jorja Smith, Lauren Hill... all those sort of artists they’re incredible.

"They are what makes the music scene so why wouldn’t you want to add it in?" Maddie says.

Maddie Juggins thinks all genres of music should be taught

A greater curriculum focus would not just boost artists, according to Paul Bonham, who feels the industry would benefit too.

"If we have subject matter which is inclusive, diverse, at some point even a bit challenging to one’s own identity, it makes us into fully rounded people," Paul, the professional development director at the music manager’s forum, says.

The UK government first laid out its national plan for music education in England in 2022.

The new review into the curriculum, which covers all lessons - not just for music education, is open for people in England to share their thoughts until 20 November.

In response, the Department for Education told the BBC "every child should be represented in what they learn at school and inspired by a rich and diverse curriculum".

Listen to Newsbeat live at 12:45 and 17:45 weekdays - or listen back here.

3 weeks ago

12

3 weeks ago

12