New Delhi, India – Every morning, Mohammad*, 32, watches his 12-year-old daughter, Fatima*, waking up with the same enthusiasm – putting on her worn-out uniform, neatly braiding her hair and sprinting to the government school in New Delhi’s Khajuri Khas area in the northeast, where they live with about 40 other Rohingya families in cramped rented rooms.

Fatima is among a handful of Rohingya children in Khajuri Khas with access to formal education in a government school. Many other children like her, including her younger brother Ahmed*, have been denied school admission for years.

As a new academic year begins next month, Fatima fears she may suffer the same fate.

On Christmas Day in December, as tens of thousands of Delhi’s pupils looked forward to a winter break, the national capital territory’s Chief Minister Atishi, who goes by her first name, posted on X: “Today, the Education Department of the Delhi Government has passed a strict order that no Rohingya should be given admission in the government schools of Delhi.”

Atishi, a former Rhodes Scholar who studied at Oxford, is a leader of the Aam Aadmi Party (Common Man’s Party or AAP), a relatively new political force in India that owes its foundation in 2012 to a popular “pro-poor” and anticorruption movement.

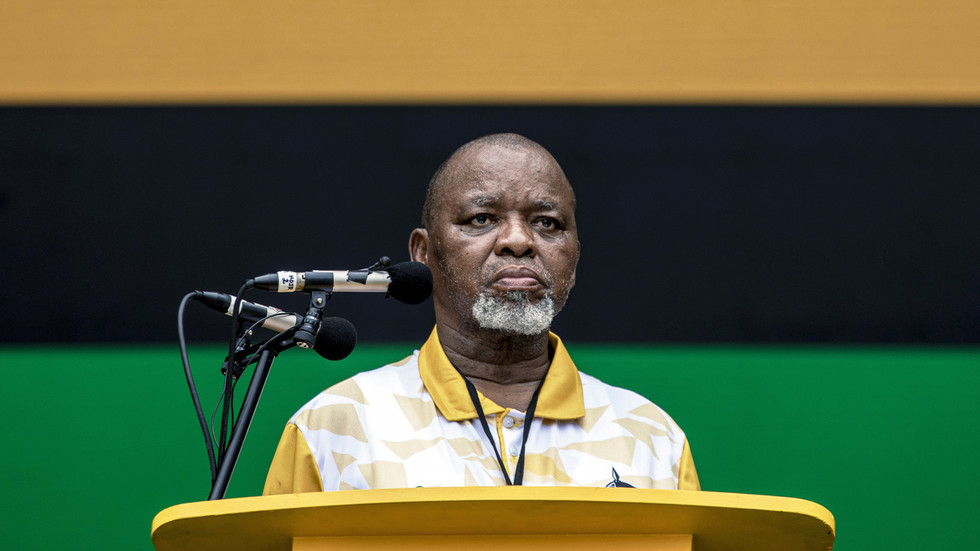

Atishi looks on during an interview with Reuters news agency in New Delhi [File: Sharafat Ali/Reuters]

Atishi looks on during an interview with Reuters news agency in New Delhi [File: Sharafat Ali/Reuters]The AAP, which has been governing the national capital territory of Delhi for more than a decade, is seeking a return to power in the provincial assembly elections to be held on Wednesday. The results will be declared on Saturday.

But this year, AAP faces a serious challenge from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which controls 20 of India’s 36 states and federally-controlled provinces (called Union Territories) – either directly or through coalition partners – but has been out of power in the national capital for more than 25 years.

‘Parties trying to outcompete each other’

On December 11, the BJP-appointed lieutenant governor of Delhi ordered a special drive to identify and act against “all illegal immigrants from Bangladesh” who may be “involved in criminal activities” in the city.

Bangladesh, India’s neighbour in the east, hosts more than a million Rohingya, a mainly Muslim ethnic group, most of whom fled what the United Nations described as a “textbook case of ethnic cleansing” by Myanmar’s military in 2017. It was the largest exodus of the community which had been fleeing state persecution in Buddhist-majority Myanmar for decades.

Nearly 40,000 Rohingya, like Mohammad, came to India in search of security and livelihoods, and settled in several parts of the country. New Delhi is home to about 1,100 of them, according to a 2019 estimate by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), most of them confined to predominantly Muslim neighbourhoods of the city.

The BJP and other right-wing groups, whose politics hinges on an anti-Muslim platform, have been attacking the Rohingya for years, accusing them of “terrorist” links and demanding their arrests and deportation from the country. Many have been put in detention centres in the capital and other parts of the country.

During a news conference on Monday, BJP spokesman Sambit Patra accused the AAP government of causing a “demographic manipulation” to affect the electoral process in the national capital. The Hindu majoritarian party has repeatedly accused the AAP of adding “illegal Bangladeshis” to voter lists in order to expand its vote base.

Addressing an election rally last week, federal Home Minister Amit Shah promised that if the BJP came to power, it “would free Delhi of illegal Bangladeshis and Rohingyas in two years”. Shah – and many in his party – have in the past referred to Bangladeshi migrants as “termites” and “infiltrators”.

Rohingya children at a refugee settlement in Madanpur Khadar, New Delhi [Quratulain Rehbar/Al Jazeera]

Rohingya children at a refugee settlement in Madanpur Khadar, New Delhi [Quratulain Rehbar/Al Jazeera]Not to be outdone by the BJP in the race for power in Delhi, the incumbent AAP government also raised the pitch against the Rohingya, in turn accusing the BJP of poor border control that facilitates their entry into the country.

On December 15, four days after Delhi’s lieutenant governor ordered a drive against Bangladeshi migrants, Atishi accused the BJP of “appeasing” the Rohingya. She referred to a 2022 social media post by federal minister Hardeep Singh Puri about relocating Rohingya refugees in government-owned apartments. Modi’s government quickly backtracked on the issue and denied issuing any such directive.

Days later, Atishi banned all Rohingya children from seeking admission to Delhi’s public schools.

“Now this [election] campaign has reached a low where both the parties are trying to outcompete each other in attacking the Rohingya,” Angshuman Choudhary, a PhD scholar at the National University of Singapore who works on migrant issues, told Al Jazeera.

Choudhary said it was the first time he saw a government systematically deny education to children.

“Earlier, there was discrimination, but humane officials at some schools would apply their minds and give admissions to kids. That scope has ended since this order has come from the top,” he said.

“Now the BJP would also not mind doubling down and proving its own anti-Rohingya credentials if cornered,” he said, adding that the trend can have “particularly devastating consequences” and a spillover effect, especially in BJP-ruled states.

“There have been many occasions when the AAP has outdone the BJP in targeting the Rohingya,” Apoorvanand, a professor of Hindi at Delhi University who also goes by one name, told Al Jazeera.

‘Our struggle for safety continues’

Caught in the electoral crossfire between the two political parties, many Rohingya say they cannot return to Myanmar. “Two weeks ago, two of my cousins in Burma were murdered by the military,” Mohammad told Al Jazeera, using the previous name for Myanmar.

He added, however, that it was becoming increasingly difficult for the community to live in Delhi.

About 25km (16 miles) away from Mohammad’s home, in the southeast corner of the city, lies Madanpur Khadar, a dusty, impoverished colony that houses a camp for the Rohingya.

Water is stored in plastic containers at Madanpur Khadar camp in New Delhi [Quratulain Rehbar/Al Jazeera]

Water is stored in plastic containers at Madanpur Khadar camp in New Delhi [Quratulain Rehbar/Al Jazeera]For eight months, the camp’s residents have been living without electricity. There are no toilets, and drinking water is supplied through tankers twice a week. Most families here rely on charity, with some of their children attending a neighbourhood school.

But in the wake of another anti-Rohingya election campaign, they are unsure about their children’s future education.

“The problem is not just the elections. This [targeting of Rohingya] has been happening for many years in India. We did not come here for politics, we came to save our lives. But sadly, it seems we cannot find peace even here. For years, we have been criminalised in the name of politics, and our struggle for safety continues without end,” Sabber Kyaw Min, a Rohingya activist and founder of the Rohingya Human Rights Initiative, told Al Jazeera.

Fatima’s father Mohammad says denying Rohingya children education is not a new phenomenon in the city. He says unlike Fatima, his 10-year-old son Faizan has not been able to join school.

“At this age, I don’t want him to feel that he is different,” Mohammad told Al Jazeera, adding that he approached at least four government schools in the last five years for Faizan. But all of them declined.

‘Deeply shameful’

Mohammad says the situation worsened in late 2019 when Modi’s government passed a controversial citizenship law and his party pushed for a national register of citizens – both seen as anti-Muslim moves that triggered nationwide protests and deadly communal riots in New Delhi in early 2020.

“Post-2020, most Rohingya children were not given school admissions,” said Mohammad, adding that the authorities started asking for government documents that refugees cannot possess. Earlier, children such as Fatima secured admission by using identity cards issued by the UNHCR.

“I have met and pleaded with the local authorities at least 25 times,” Mohammad said. “They ask for Aadhaar [India’s biometric ID] cards. We don’t have them and we cannot get one because that would be illegal.”

In October last year, Social Jurist, a New Delhi-based NGO, filed a petition before the Delhi High Court, asking why Rohingya children were being denied education when the same rights were available to refugees from other countries. The petition was dismissed.

The NGO approached the Supreme Court, which held a hearing last week, in which it asked the petitioners to find out if the Rohingya lived in makeshift camps or regular neighbourhoods. The top court will next hear the matter later this month.

“Even in Delhi, where education was previously accessible, this exclusion is now taking place. It is deeply shameful that highly educated individuals take pride in barring these children from schools,” New Delhi-based Rohingya activist Ali Johar told Al Jazeera.

“Now, I realise the importance of education,” says Ali’s brother, Salimullah. Their sister, Tasmida, is the first Rohingya female graduate from India and is now pursuing her master’s in politics from Canada’s Wilfrid Laurier University under a UNHCR-Duolingo programme.

Tasmida Johar [File: Aliza Noor/Al Jazeera]

Tasmida Johar [File: Aliza Noor/Al Jazeera]“Earlier my family and I were opposed to her education but our brother [Ali] insisted on it and supported her throughout. Today, she has made us proud and also supports us,” said Salimullah.

Mohammad says that is why he wants his kids to be educated.

“It is the only way for our progress. I cannot read and write. But I feel proud when my daughter reads phone messages for me and replies in English,” he said.

Since Atishi’s order, Fatima has been pleading with her father to get her admitted to a private school. Mohammad, a daily wage worker who also depends on aid from charities, cannot afford the exorbitant fees at private schools.

But he hopes the Supreme Court will come to his rescue. “The Indian law treats people fairly,” he says.

When asked what profession Fatima wants to pursue in future, he said: “She wants to become a teacher … She will teach everyone that all kids are kids – and equal.”

*Names changed to protect their identities

2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2