BBC

BBC

Work and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall is set to unveil details of how the government plans to cut billions of pounds from the working-age welfare bill.

The focus will be on reducing spending on health-related and disability benefits.

That bill is rising rapidly and many argue it needs to be curbed for the sake of the UK's public finances – as well as the economic and individual benefits of getting people back into work.

But this is not the first government to seek savings from the welfare budget, and to try to encourage more people into employment.

And charities are warning about the adverse impact on vulnerable recipients.

There are three broad approaches which the government is believed to be examining:

- Cutting the level of benefit payments

- Tightening the eligibility for benefits

- Attempting to get people off benefits and into work

BBC Verify has examined the past 15 years of policies in this area to see what might be effective – and what risks being counterproductive.

Cutting payments

The working-age health and disability benefits bill has certainly been increasing in recent years, and is rising rapidly.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the official forecaster, has projected that total state spending on these benefits for people in the UK aged between 18 and 64 will increase from £48.5bn in 2023-24 to £75.7bn in 2029-30.

That would represent an increase from 1.7% of the size of the UK economy to 2.2%.

By 2030, around half of the expenditure is projected to be on incapacity benefit, which is designed to provide additional income for people whose health limits their ability to work.

The other half is projected to be on Personal Independence Payments (PIP), which are intended to help people of working age with disabilities manage the additional day-to-day costs arising from their disability.

One straightforward way for ministers to curb this projected rise would be to hold payments flat in cash terms, rather than allowing them to rise in line with prices each year.

"Reducing award amounts is the easiest way to get savings in the short term," says Eduin Latimer of the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Freezing incapacity benefits in cash terms until 2030 would save £1bn a year, according to the Resolution Foundation.

But you can only receive incapacity benefit if your income and savings are below a certain level, so freezing payments would impact people who are worse off.

Also, people on disability benefits such as PIP are considerably more likely to be in poverty and material deprivation.

Under previous governments between 2014 and 2020, most working-age benefits did not rise in line with inflation - to save money.

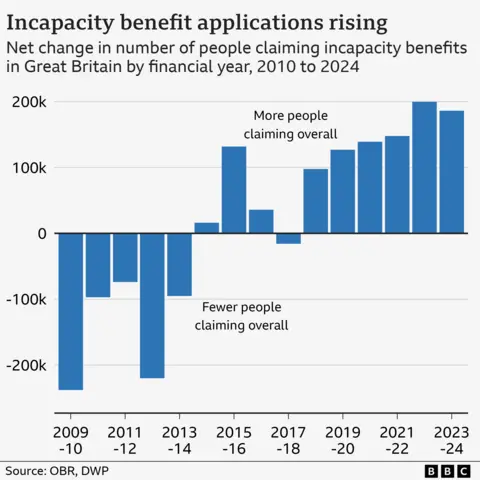

And from 2015, more and more people claimed incapacity benefit.

So cutting the value of individual payments might save some money up front, but still not have a dramatic impact on the overall bill in the longer term if claimants continue to rise.

Tighten eligibility

Rather than cutting the value of these benefits for all recipients, the government could seek to save money by making it harder for people to claim them in the first place.

For instance, the previous government had proposed making it harder for people with mental health conditions to claim PIP, arguing that the monthly payment was not proportionate to the additional financial needs created by their conditions.

But it is important to note that efforts to change the eligibility criteria for these benefits over the past 15 years have not yielded the results hoped for.

PIP was introduced in 2013 to replace the old Disability Living Allowance, with the intention it would lead to savings of £1.4bn a year relative to the previous system by reducing the number of people eligible.

PIP was initially projected to reduce the number of claimants by 606,000 (28%) in total.

Yet the reform ended up saving only £100m a year by 2015 and the number of claimants rose by 100,000 (5%).

Another attempt in 2017 to limit access to PIP was also reversed.

The reason was that many people appealed against refusals that had been triggered by the tightened eligibility criteria. Also, the emergence of cases in the media which seemed unfair meant ministers, often under pressure from their own backbench MPs, ultimately ordered the eligibility rules to be relaxed.

Official decisions not to award PIP and incapacity benefit to claimants are still often challenged and around a third of those challenges are ultimately upheld at an independent tribunal.

"Britain's chequered history of benefit reform shows that the government should proceed cautiously, rather than rush ahead to find savings which could backfire," says Louise Murphy of the Resolution Foundation.

Encourage work

Another way for the government to try to achieve savings is by encouraging more people to come off these benefits and enter work.

Around 93% of incapacity benefit claimants are not in work and the same is true of 80% of PIP claimants.

One potential route to increase employment rates could be regular reassessments of people in receipt of incapacity benefit and a requirement for them to start looking for jobs if they are found to be fit for work.

The fall in the number of people claiming incapacity benefit in the early 2010s has been attributed by the OBR to reassessments of a large number of people in receipt of an older form of the benefit.

However, an aggressive or onerous reassessment regime could risk imposing distress on people who are unable to work and could also create unexpected distortions in the system.

The OBR has suggested the sanctions introduced to the wider benefits system by the last government, requiring people judged fit to work to be actively looking for employment or risk losing their benefits, had the counterproductive effect of increasing the incentive for people to try to claim incapacity benefits (for which these work-searching requirements did not apply).

Another potential policy avenue to boost employment rates is through providing much greater support to find jobs.

Some advocate increasing government investment in official schemes, working with employers, to help people to enter the workplace.

There have been various schemes designed to achieve this over the past 15 years, though they have not been on a large scale.

Evaluations have shown some positive employment effects from them.

However, the OBR concluded last year that the evidence base was still limited and did not suggest such programmes have, so far, made a "significant contribution" to getting people into work.

That implies the official forecaster may hesitate to assume greater state investment in these schemes will pay for itself through higher employment and tax revenues, and result in net savings in public expenditure.

Nevertheless, some experts argue it would make sense for the government to re-assess more regularly whether people in receipt of health and disability benefits are still unable to work and - if their circumstances are found to have changed - to provide them with additional support to get into the workforce.

"Not doing reassessments and work-focused interviews definitely makes things worse," says Jonathan Portes, a former chief economist at the Department for Work & Pensions.

3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2