Theo Leggett

International business correspondent

BBC

BBC

For decades, car-making has been the jewel in Germany's industrial crown, a powerful symbol of the country's famous post-war economic miracle. Its "Big Three" brands, Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, and BMW, have long been praised for their performance, innovation and precision engineering. But today, the German motor industry is struggling. How can it get back on the road to recovery?

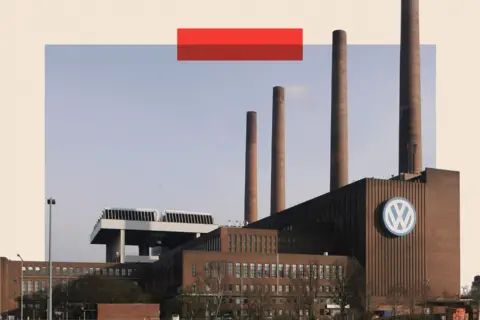

When you arrive by train in Wolfsburg, Lower Saxony, the first thing you see is the Volkswagen factory. Its huge facade, emblazoned with a giant VW logo and flanked by four tall chimneys, dominates one bank of the canal that runs through the city. The 6.5 sq km (2.5 sq mile) complex sits adjacent to the Autostadt, a kind of theme park devoted to the automobile and to VW, Europe's biggest carmaker. The Volkswagen Arena, a sports stadium, is a short distance away.

Wolfsburg is Germany's answer to mid-20th Century Detroit - not so much a city with a car factory as a factory with a city that has grown up around it. Some 60,000 people from across the region work in the plant, while the town itself has a population of around 125,000. Locals say that even if you don't work in the factory yourself, it's certain many of your friends will, along with half of your class from school.

Getty Images

Getty Images

When you arrive by train in Wolfsburg one of the first things you see is the Volkswagen factory

"Wolfsburg and Volkswagen - it's kind of a synonym," explains Dieter Landenberger, the VW Group's in-house historian, as he looks lovingly at an early model Beetle. It is one of an array of beautifully restored classic cars in the Zeithaus – a huge, glass-fronted museum in the Autostadt dedicated to icons of the motor industry.

"We're proud of the plant," he says. "It is a symbol of that period in the 1950s when Germany had to reinvent itself and rebuild after the war. It was a kind of motor for the German economic miracle."

Today, however, the plant has also come to symbolise some of the main problems affecting the German car industry as a whole. The Wolfsburg factory is capable of building 870,000 cars a year. But by 2023 it was making just 490,000, according to the Cologne-based German Economic Institute. And in Germany it is far from alone. Car factories across the country have been operating well below their maximum capacity. The number of cars produced in Germany declined from 5.65m in 2017 to 4.1m in 2023, according to the International Organisation of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers.

Car-making makes up about a fifth of the country's manufacturing output, and if the supply chain is taken into account, it generates around 6% of GDP, according to Capital Economics. The industry employs some 780,000 people directly – and supports millions of other jobs.

It's not just production that is down. Sales of cars made by German brands are far lower than they were just a few years ago. Between 2017 and 2023, those of VW fell from 10.7m to 9.2m, while over the same period BMW's went from 2.46m to 2.25m and Mercedes-Benz's went from 2.3m to 2.04m, company reports show.

All of the Big Three saw their pre-tax profits fall by about a third in the first nine months of 2024, and each warned that their earnings for the year as a whole would be lower than previously forecast.

The development of electric cars has sucked up huge investment, but the market for them hasn't grown as quickly as expected, while foreign competitors are flexing their muscles. The threat of tariffs being imposed by the US and other governments also looms large.

"There are so many crises, a whole world of crises. When one crisis is over, another is coming up," is how Simon Shütz, a spokesman for the German Automotive Industry Federation (VDA) puts it.

Car sales across Europe have been declining since 2017, according to Franziska Palmas, a senior Europe economist at Capital Economics. "Lately they've recovered a bit, but they're still around 15 to 20% lower than they were at the peak in 2017," she says. "That's partly due to factors like the pandemic, the energy crisis. But it's also cars lasting longer - and people already have a lot of cars in Europe. So demand has been weak."

Electric dreams

Another key factor has been the aforementioned transition to electric cars. Since the diesel emissions scandal of 2015 – in which VW was found to have rigged emissions tests in the US – the industry has been undergoing a technological revolution.

With the EU and European governments determined to phase out petrol and diesel cars over the next decade, manufacturers have had little choice but to invest tens, and collectively hundreds of billions of Euros on developing electric models and building new production lines.

However, although electric cars do now make up a significant share of all cars sold – 13.6% in the EU and 19.6% in the UK last year, for example – their market share has not been growing as quickly as anticipated.

Getty Images

Getty Images

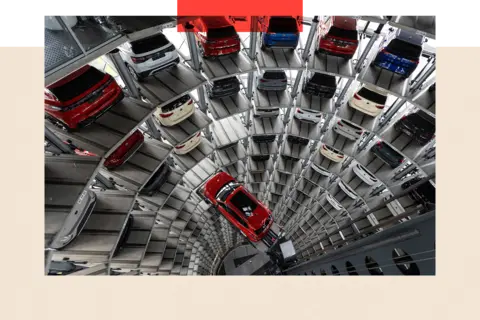

Car-making makes up about a fifth of Germany's manufacturing output

And in Germany itself, the sudden removal of generous subsidies for electric car buyers in late 2023 actually contributed to a dramatic 27% fall in sales of all electric cars within the country last year, making life still more difficult for German firms in their home market.

"The decision to drop subsidies suddenly – that was very bad, because it undermined trust among our customers," says the VDA's Simon Schütz.

"Going from the combustion engine to electric mobility is very big process. We are investing billions in rebuilding all the factories. And so that takes some time, there's no question about it."

An expensive business

While all of this has been going on, German manufacturers have also been grappling with another serious concern. Doing business in Germany itself, operating factories here and employing hundreds of thousands of people, is very expensive.

Workers in the automotive sector have traditionally enjoyed generous pay and benefits thanks to agreements drawn up between unions and management. According to Capital Economics, in 2023 the average monthly base salary in the German auto industry was about €5,300, compared with €4,300 across the German economy as a whole.

For years, this approach gave German-based companies certain advantages, for example in avoiding industrial unrest and in attracting and retaining talented staff. However, it also led to German car manufacturers having the highest labour costs in the global industry. In 2023, these averaged €62 per hour, compared to €29 in Spain and €20 in Portugal, according to the VDA.

The situation for Germany's domestic car industry became more acute following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. This choked off Germany's once-abundant supplies of cheap Russian gas, at the very time when the country was phasing out nuclear power.

The result was a sharp increase in energy prices. Although they have since subsided, energy costs for industrial users in Germany remain very high by international standards. "Energy prices here are three to five times higher than in the US, or in China – much higher than for our main competitors," says Mr Schütz.

And this is being felt across the industry, not just at the carmakers themselves. "From the Thysenkrupp and Salzgitter steel mills producing the sheet metal rolls that are later turned into doors and bonnets, to makers of smaller components used in drivetrains, costs have exploded as a result of high energy prices," says Matthias Schmidt of Schmidt Automotive Research.

'A very big shock'

Last year these pressures came to a head. At VW, which has 45% of its global staff in Germany, managers finally decided radical action was needed to bring down costs.

"It was a very big shock," IG Metall union spokesman Steffen Schmidt tells me over a cup of coffee near the WV factory in Wolfsburg. "The company didn't say anything publicly."

It was left to Daniela Cavallo, head of the powerful VW works council and the top employees' representative, to deliver the news. "They held a big meeting outside the gates of the factory. Thousands of workers – and you could have heard a pin drop," says Mr Schmidt.

"They were stunned. Thousands of people, all completely silent."

Getty Images

Getty Images

Not all of the German car industry's problems are confined to Germany itself

What VW proposed was unprecedented. Union representatives had come to meetings expecting to negotiate an annual pay rise. They were asking for a 7% boost. Instead, they were told, the company needed them to take a 10% pay cut.

Worse was to follow. The company said it might have to close up to three of its factories within Germany itself – and was tearing up a job security agreement that had been in place for decades.

Arne Meiswinkel, WV's chief negotiator, said at the time that the situation it faced in Germany was "very serious" and that "Volkswagen will only be able to prevail if we future-proof the company now in the face of rising costs and the massive increase in competition".

Volkswagen had never previously closed a German factory in its 87-year history. In the face of intense opposition from unions and politicians, and following short but disruptive "warning strikes" by unionised workers, the idea was ultimately shelved. But the very fact it had been put forward sent a seismic shock through the entire sector.

In the meantime, the workforce did agree to painful limits on pay and bonuses, and VW said it would cut more than 35,000 jobs by the end of the decade, albeit in a "socially responsible manner" that avoided compulsory redundancies.

Less conspicuously, Mercedes-Benz also launched a cost-cutting drive last year, aimed at saving several billion euros annually - albeit compulsory redundancies in the German workforce are highly unlikely, as a job security agreement effectively rules them out until 2030. Meanwhile Ford, which operates two factories in Germany, recently announced plans to cut 2,800 jobs in the country.

Not all of the German car industry's problems are confined to Germany itself. With the European market saturated, for several decades the continent's manufacturers have looked for growth elsewhere.

The impact of China

One of the most lucrative markets has been China, where for a while the growing middle class had an apparently insatiable appetite for upmarket European vehicles. VW, Mercedes-Benz and BMW all teamed up with local businesses, setting up factories in China itself to meet local demand.

But now that source of growth is drying up. The Big Three have all seen sales fall recently – in 2023 VW's China sales were down 9.5% on the previous year, Mercedes-Benz's by 7% and BMW's by 13.4%. Their combined share of the Chinese market has shrunk as well to 18.7%, from a peak of 26.2% in 2019. This appears to be the result of a slowing Chinese economy, falling interest in expensive, foreign-badged cars and the rapid growth of local marques, especially in the electric car market.

"Not that long ago, Western brands represented quality and trust," explains Mark Rainford, founder of the Inside China Auto website. However, he says, since then the reputation and appeal of Chinese brands has improved beyond recognition.

All of the Big Three say trends in China have had a significant impact on their earnings.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Sales of cars made by German brands are far lower than they were just a few years ago

Chinese brands are also attempting to build a share of the European market, helped by their much lower operating costs than more established rivals, both because wages are lower in China and because, as pure EV firms, they don't have the same legacy costs carried by manufacturers making the transition from petrol and diesel to battery-powered cars.

According to the European Commission, Chinese brands also benefit from hefty government subsidies, which allow them to sell cars at artificially low prices. In October, the EU introduced extra tariffs on imports of Chinese-made EVs, in an effort to create a more level playing field.

Trade wars?

German firms opposed the EU tariffs, because they feared retaliation from China could affect their own exports. Now they also face the threat of new protectionist measures being introduced by the Trump administration, including possible tariffs on cars shipped from the EU. For an industry that relies heavily on exports, the rise of protectionism is a growing threat.

"We know that trade wars only create losers on both sides. Tariffs will cost wealth, cost growth and cost jobs," says the VDA's Simon Schütz.

Although some of the pressures facing Germany's car companies were not foreseeable, there was still an element of complacency, believes analyst Matthias Schmidt: "They knew the structural issues were there, but were blindsided by cheap Russian gas," he says.

Getty Images

Getty Images

All of the Big Three say trends in China have had a significant impact on their earnings

"The expansion to China and the high profits being shipped back to Europe plastered over the high labour cost issues, giving unions a joker card to play with.

"Germany has effectively been an export-driven market, and once those markets sneeze, Germany catches a cold, which is what's happened."

A high-stakes challenge

So can Germany's carmakers revive their fortunes? It is a vital question for the manufacturers, for their networks of suppliers and for the country as a whole.

"The problem for Germany is we are not competitive," says Dr Ferdinand Dudenhöffer, head of the Bochum-based Center for Automotive Research. "Not just in cost terms, but also in terms of the new technologies which will run the world in future".

He thinks China has become the centre for gravity for innovation in areas such as digitisation and battery technology. "The solution for the carmakers and for the suppliers, in my view, will be that they take their factories abroad," he says.

Simon Schütz is more optimistic. He thinks the industry can prosper, but only if it gets the support it needs from the government after the elections later this month.

"Our automotive industry will be world-leading, I am sure of that," he says.

"The question is, where will the future jobs be? Will they be in Germany, because we can build cars here, or will our companies go elsewhere?'

For union rep Steffen Schmidt, however, the solution is to go back to Germany's traditional industrial values. "We have to become a leader in innovation and technology again," he says. "Then we can keep high pay and good conditions for workers."

He thinks the path ahead for the new government is very clear: "Invest, invest, invest. In infrastructure, in technology, in green energy and in education."

For tens of thousands of workers in Wolfsburg, and in Germany's other "car towns" such as Ingolstadt, Weissach, Munich, Stuttgart and Zwickau, the stakes could not be higher.

Top picture credit: Getty images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3