Just now

Sarah Rainsford,Eastern Europe correspondent

BBC

BBC

Many children like Angelina are having to adapt to the conditions of war the best they can

At 12 years old, Lera is learning to walk again. Timid steps at first, but more confident with each one she takes.

Last summer a Russian missile attack shattered one of her legs, and left the other badly burned.

Close to 2,000 children have been injured or killed in Ukraine since Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale invasion. But the war doesn’t always leave visible scars like those that run up Lera’s leg.

“Almost every child has problems caused by the war,” says psychologist Kateryna Bazyl. “We are witnessing a catastrophic number of children turning to us with different unpleasant symptoms.”

Right across Ukraine, young people are experiencing loss, fear and anxiety. An increasing number struggle to sleep, have panic attacks or flashbacks.

There’s also been a surge in cases of child depression among a generation growing up under fire.

Lera Vasilenko, 12, in Chernihiv, northern Ukraine

Lera has had to learn to walk again after being injured by a Russian missile

Lera saw the missile that hurt her seconds before it hit.

It was a hot summer holiday and the centre of Chernihiv was busy. She and her friend, Kseniya, were trying to sell their homemade jewellery to the passing crowd.

“I saw something flying from up to down. I thought it was some kind of plane that would go up again, but it was a missile,” Lera says, the words tumbling out at high speed like she doesn’t want to dwell on their meaning.

After the explosion, she ran back and forth in panic on her mangled leg before she realised she’d been injured.

“People say I was in a state of shock. It was only when Kseniya said, ‘Look at your leg!’ that I felt the pain. It was awful.”

At the start of all-out war in 2022, the bombardment of Chernihiv in northern Ukraine was constant. But within weeks, the Russian forces had been pushed back. Life slowly returned to the city.

Then, on 19 August 2023, the local theatre hosted an exhibition of drone manufacturers, and Russia attacked. Shards of metal sliced through the streets all around.

Nine months later, Lera lifts her trouser leg to reveal multiple deep scars and a skin graft. There’s a big bump where metal implants were inserted.

The wounds are healing well and she moves nimbly on her crutches. But she still struggles with the sound of air raid sirens.

“If they say there’s a missile heading for Chernihiv then I go crazy,” she admits. “It’s really bad.”

Deep scars can be seen on Lera's leg - although the wounds are healing well

She insists she’s coping, and hasn’t changed, but her sister isn’t so sure. “You’re more explosive,” Irina tells her. Lera nods sheepishly. “I wasn’t so aggressive before.”

It’s one of many reactions that child psychologists are seeing to the stresses of this war.

“Children don’t understand what’s happened to them, or sometimes the emotions they feel,” explains Iryna Lisovetska, from the Voices of Children charity that’s helping hundreds of young Ukrainians across the country.

“They can show aggression as a form of self-protection.”

For Lera, the war has been doubly cruel.

A few months before she was injured, her brother was killed fighting on the front line. The two were close and Lera still struggles to accept that Sasha has gone.

“I imagine he’ll call at any moment. I used to see his face in passers-by on the street. I still can’t believe it,” she confides quietly, wrapped in a Ukrainian flag she plans to take to Sasha’s grave. A replacement for one frayed by the wind.

Lera's brother was killed on the front line just months before she was injured

Without warning, Irina taps her phone and Sasha’s deep voice fills the room. “I really love you,” the soldier assures his sisters in a last audio message sent from the front.

It’s the first time Lera’s heard his voice since he died. Her chin trembles with emotion.

Daniel Bazyl, 12, in Ivano-Frankivsk, western Ukraine

Daniel is getting drawing advice remotely from his dad, who is on the front line close to Kharkiv

Daniel’s greatest fear is to experience a loss, like Lera.

His father is a soldier, serving close to their hometown of Kharkiv where the fighting has intensified.

Russian troops recently crossed the border in a surprise offensive, taking new ground, as missile attacks on the city have increased. Among those killed in just the past week was a 12-year-old girl, out shopping with her parents.

“Dad tells me it’s all ok, but I know the situation there is not the best,” Daniel says. “Of course I worry about him.”

The 12-year-old now lives in western Ukraine with his Mum, a world away from Kharkiv. Russian missiles do reach Ivano-Frankivsk but you get a lot more warning. The streets are crowded and relaxed. There’s even traffic jams.

But even here, Daniel can’t escape the conflict. He’s taped a prayer above his bed which he recites each night for his father’s safety, though he was never religious before.

Daniel and his mum, Kateryna, left their home in Kharkiv after the war began

He and his mum, Kateryna, were refugees for a while. They returned to Ukraine because she’s a child psychologist and saw the urgent need for her skills.

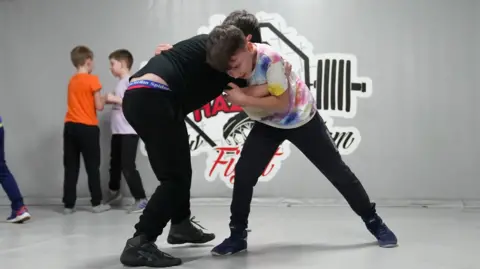

She does her best to keep her own son distracted with endless activities: there’s a skate park and guitar classes. He went busking to raise money for the Ukrainian military and there’s a fight club to help him stand up to the school bullies.

“I tried to find things he loved before, to continue doing here, and it works,” Kateryna says.

Now in western Ukraine, Daniel keeps himself busy with wrestling classes and skateboarding

But the boy from the north east still struggles to fit in.

“It really bothers me when there’s an air raid at school and everyone’s happy they’ll miss class,” Daniel says. “Here, a siren just means going to the bunker. But it actually means there’s fighting somewhere else in Ukraine.”

Daniel counts the hours between online calls with his dad. His father has been sending parcels full of art materials so that he can teach him to draw, remotely.

“I want to believe the war will end soon,” Daniel shares his greatest desire. That way, he could go home to Kharkiv, he says.

“And that would be really cool.”

Angelina Prudkaya, 8, in Kharkiv, north-eastern Ukraine

This should have been Angelina's school - a hole has been blown through the side

Eight-year-old Angelina is still in the city, living in the middle of a bomb site.

She’s from the Saltivka suburb, which is Daniel’s home too. When Russian troops first advanced in the region two years ago, it was right in the firing line and Angelina was sheltering with her family in their basement.

“It was very scary. I just thought, when will it all end? There were rockets and a plane flew over us,” the little girl recalls, tugging at the sleeves of her sweater.

In early March 2022, the giant block of flats next door was destroyed by a missile.

Angelina’s mum, Anya, told her to block her ears and lie quietly.

“I thought we’d be buried beneath the ruins. That our building had been hit, and would collapse,” she says, eyes wide at the memory.

After that they fled.

But when Ukrainian forces liberated the northern region last year, the family returned to Saltivka. They’re the only people living in their block of flats, surrounded by smoke-blackened buildings and smashed glass. Despite the shrapnel holes in the kitchen wall, it’s home.

Angelina sheltering in the basement of her home when Russian troops first advanced two years ago

Now Kharkiv is a nervous place again. The glide-bomb attack on a DIY store last weekend was close to Angelina’s flat.

Vladimir Putin says he has no plans to try to take the city but Ukrainians have learned never to trust him.

“When they start to bomb, I tell mummy I’m going to the corridor and she sits there next to me,” Angelina says, with the calm of too much experience.

Moving to the corridor puts an extra wall between your body and any explosion. It’s minimal protection.

Angelina should have started at her local school by now, but it has a hole blown through the side. She barely remembers kindergarten because before the invasion, there was Covid.

Anya tries to counter the solitude by taking her daughter to activity sessions, including pet therapy. It’s run by the children’s charity Unicef, underground on the metro for extra safety.

Throwing balls for a shiny dog called Petra, Angelina comes to life in fits of giggles.

Pet therapy sessions run by the UN are giving children a welcome distraction from the stresses of war

But when evening falls over her home, the lights don’t come on anymore. Russia has been targeting the power supply.

So Angelina lights a candle, carefully, her small figure casting a giant shadow on the wall of their flat. “It happens all the time,” she shrugs, about the blackouts.

Like Lera and Daniel, Angelina is adapting to this war as best she can.

But across the country, there’s growing demand for support.

“We tell the children it’s ok to feel whatever they do,” Kateryna Bazyl explains. “We say we can help them understand how to control these emotions, not to destroy everything around them. Or themselves.”

When I wonder whether there’s enough help to go round, she pauses.

“To be honest, we have a really big queue.”

Production by Anastasia Levchenko and Hanna Tsyba

Photos by Joyce Liu

6 months ago

23

6 months ago

23