Getty Images

Getty Images

At first “John” was flattered when a woman reached out to him on social media, and sent him “kind and supportive” messages.

“Then they started to get flirty,” says John, who has a learning disability and asked to remain anonymous.

The woman, who said she was a teacher, began sending him intimate photos and convinced him to do the same. But after he sent one back, her tone shifted.

“All of a sudden, you are pressured to do something and you do it without thinking,” says John. “That’s all they needed then to blackmail me.”

Soon, the messages became unrelenting - as many as 50 a day.

“You dare block me on twitter... see my next move,” said one. “You think you can run away? I still have your picture,” another read.

The person demanded money and threatened to share John’s image online, a crime commonly referred to as sextortion. John lost more than £3,000 trying to stop the blackmailer from sharing the image.

When he had no more money to offer - fearing there was no way out - John thought about taking his own life.

“I thought my life was over,” he says. “I thought they are going to ruin me.” He says that’s when he finally decided to tell someone he could trust.

John reached out to a charity, which he knew supported people with learning disabilities. Kat Akass, at SeeAbility, was the first person he spoke to.

“I don’t think you can picture how bad it was unless you were there,” she says. “We were really concerned about his personal safety. He was so distressed. He really, honestly thought his life was over.”

There are no official statistics around the number of sextortion cases in the UK. So BBC News sent a Freedom of Information Act request to every police force in the UK, asking how many reported blackmail offences featured the word "sextortion” over the last decade.

The 33 forces (out of a total 45) who responded recorded almost 8,000 blackmail cases logged with a reference to sextortion last year. The same number of forces recorded 23 in 2014. All the forces to respond were in England and Wales.

Across the last decade, there were at least 21,323 recorded offences that included a reference to the word sextortion. Over 18,000 of these were since the pandemic.

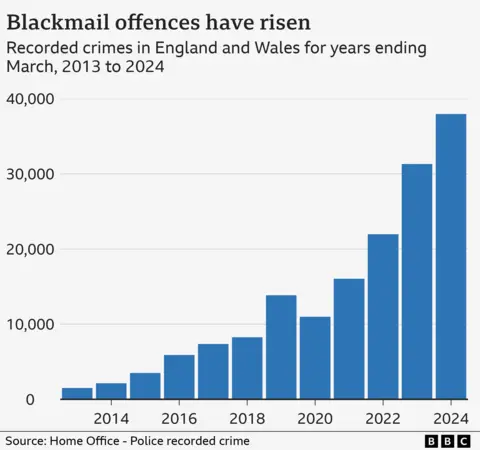

In the same timeframe, blackmail offences as a whole have seen an 18-fold rise, according to Home Office data.

Earlier this year, the National Crime Agency (NCA) put out its first ever all-school alert, warning teenagers about the dangers of sextortion. The NCA knew it was a rapidly rising crime, but said it didn’t know how many victims were out there.

The BBC showed John’s interview and the police data to Sean Sutton from the NCA's child sexual abuse threat team.

“It’s just devastating,” he said. “And we know that a number of people have already taken their own lives in the UK.”

In fact, the NCA is so concerned that they’ve spoken to the coroner’s office to suggest that, in cases of suicides with no apparent motivation, they should explore the possibility of sextortion.

The data obtained by the BBC is imperfect. It’s difficult to know exactly how many victims are out there, as this type of criminality has, until now, been reported by police under a number of different offences, mostly blackmail but also cybercrime, and child abuse.

Officers may also have recorded it using a description other than “sextortion”. But that is about to change.

Such is the scale of this issue, the NCA is about to start identifying this as a crime in its own right. It will be called financially-motivated sexual exploitation and given its own unique crime code, which will finally allow the NCA to track how widespread it really is.

Mr Sutton fears any data only reflects the tip of the iceberg because people are so reluctant to report these crimes.

“People think they’ll pay an amount of money and these criminals will go away,” he said. “Unfortunately, that’s not our experience.”

He advises victims not to be drawn into conversation with people making threats to them online: “If they ask for money, don’t pay it or you’ll end up paying more and more and more.”

Staff at SeeAbility tried to help John by reporting the flood of messages and threats as they appeared.

“You can’t get on to a real person to shut them down,” says Kat Akass. “You click a button and hit report... and then you wait.”

Rot in hell

Today, John is receiving therapy and says he lives in a constant state of anxiety. The power struggle with the scammers felt unending: reporting and blocking scammers and ignoring demands for cash.

In the end, he went to the police but he says he was made to feel like a criminal. The NCA told us this should not have happened and it plans to shortly issue new guidance for all forces.

“We do understand the stigma in these cases,” a spokesperson told the BBC. “We’re trying to take the stigma out and tell victims directly: ‘Get some help. Get some support. It’s not your fault’.”

Last week, two brothers from Nigeria who targeted a 17-year-old in a sextortion scam were sentenced to 17 years and six months in jail in the US.

The Ogoshi brothers, from Lagos, lured Jordan DeMay into sending them explicit images by pretending to be a girl his age - then blackmailed him.

The teenager killed himself less than six hours after they started talking on Instagram.

His was one of at least 27 suicides linked to sextortion in the US alone.

John wants other victims not to be afraid to tell someone what is happening to them.

“To the scammers, I say I hope you rot in hell for what you’ve done to me. But I’m speaking because I want people to know you can survive this. You just need to reach out for help.”

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this story, you can get help and support at BBC Action Line.

3 months ago

18

3 months ago

18