Huw ThomasBBC Wales correspondent

Getty Images

Getty Images

The collapse of a colliery tip above Aberfan crushed Pantglas Junior School and nearby houses, killing 116 children and 28 adults

This story contains upsetting details that some may find distressing

Even after 60 years, Mair Morgan can still remember the face of the little girl with "beautiful black curly hair" whose body she had to identify.

In the wake of the Aberfan disaster - when a colliery spoil tip collapsed, slid down a mountain and engulfed the village's primary school and surrounding houses - teachers were asked to confirm the names of the dead children before they were cleaned up and their parents told.

"I don't like the month of October at all, because that's what brings it back," said Mair.

Now 84, Mair is one of the few surviving adults who witnessed the horrors of 21 October 1966.

She had worked at Pantglas Junior School for a year when the disaster happened.

That day it was her job to ring the bell to bring children into class.

"Ever since I remember, I always wanted to be a teacher, I think it was because my aunt was a teacher."

Her childhood ambition took her to her first teaching job in England before returning to the area where she was raised to teach in Aberfan.

Mair, who was 25 at the time, remembers the joys of that first year teaching back in south Wales: "I loved it. It was a happy school."

BBC/Getty Images

BBC/Getty Images

Mair Morgan had "always wanted to be a teacher," ever since she was little

The morning of the disaster, unbeknown to those at the foot of the mountain, the large tip had been made unsteady by a build-up of water.

Then, at 09:15, the 150,000-tonne pile of slurry came roaring down the slope, crashing into the primary school and engulfing the building.

"I heard this terrible noise," said Mair.

Her classroom was in a separate building from the main school and, through the windows, she saw a playground wall had collapsed so she instinctively gathered her pupils and led them out.

She walked them down to the steps by the main road and stood with them, trying to keep calm as mothers began rushing to the school: "If you're calm, they're calm as well."

One by one, the children were collected and while her pupils had escaped the devastation of the slurry, some of their families had not been so fortunate.

"A little boy in my class lost his mother and sister," she recalled, adding that he had to be picked up by his aunt.

She also remembered a teacher from another school, Bill Evans, whose house was next door to Pantglas.

"He lost his wife, baby, and his son - who should have been in school but had tonsillitis so was home. He lost his complete family."

Only later did the scale of what happened become clear.

Five of Mair's fellow teachers were among the dead - only four of the staff survived.

In the hours and days that followed she and two other colleagues kept returning to Aberfan, even as police restricted access to the village.

"We felt we needed to be there. You felt you ought to be doing something."

Inside the school playground, a temporary shelter was used to lay out the first bodies recovered from the debris.

The teachers who had escaped were asked to perform a tragic task - identify the dead children.

"They opened Bethania Chapel as a place to take the children. But before that, in the playground, there was a shelter from the rain.

"The first bodies they brought out, they put in there, and the sadness was that they asked us could we identify these children before they were cleaned up and before their parents were told.

"I found that very hard. Thinking back, in this day and age, they wouldn't have asked you to do it."

She still remembers one little girl's face.

"She had beautiful black curly hair," she said quietly.

It soon became clear that the loss of life was too great to ask the teachers to continue their task but Mair - along with two others - Hettie Williams and Rennie Willams - kept offering comfort and support.

Fellow teacher Howell Williams, who smashed a window to help his students escape, was collected by his family from the chaos of the village.

"We went to visit the parents of the bereaved and that was very sad but we needed to do things like that," Mair said.

She believed that they, without formal counselling, provided each other with the emotional support to get through the disaster, maintaining a close bond for life.

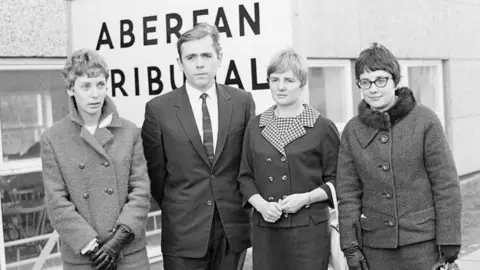

Getty Images

Getty Images

Hettie Williams, Howell Williams, Rennie Williams and Mair Morgan were the only teachers to survive the disaster

After a short break to London arranged by the National Union of Teachers, Mair returned to Aberfan.

Classes resumed in makeshift settings with children of all ages learning together.

"[It] was very informal. We read with the children, did a little bit of work, just trying to get back to normal," she said.

Hettie and Rennie moved on, but despite everything, Mair stayed in Aberfan, where she felt "rooted".

To this day, she lives just outside the village and former pupils still stop her in the street.

Staying, she believed, helped her cope.

"I loved the children," she said.

"And children are resilient, especially young ones. It was in the parents that you could see the sadness."

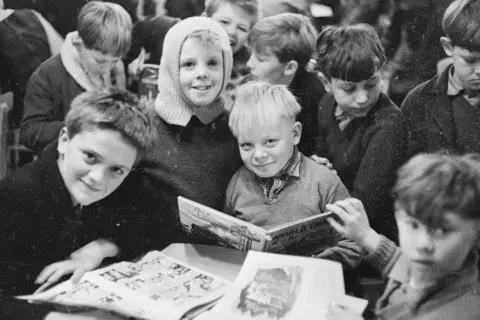

Getty Images

Getty Images

Mair Morgan cared for some of the surviving children who returned to informal lessons in temporary buildings

The Aberfan disaster led to lasting changes in how industrial waste was managed in the UK.

For those who lived through it, the looming anniversary is an important moment to ensure the lessons of Aberfan are not forgotten, but it's also a deeply personal time for those who were there.

"The only time it affects me is in October," Mair said.

"I don't like the month of October at all, because that's what brings it back."

Having rarely spoken publicly about the disaster, Mair has also watched as the story of Aberfan is repeated, and sometimes, skewed.

She is clear about one detail that still matters to her and wanted to correct a persistent myth - that children were singing All Things Bright and Beautiful in assembly when the tip collapsed.

"There was no assembly that morning. If there had been, there would have been no survivors."

That would have been because everyone would have been gathered in the main hall and the colliery tip would have collapsed on top of them.

Getty Images

Getty Images

A memorial garden replaced the ruined junior school and is the focal point for remembering those who died in the disaster

Assembly was planned for the afternoon, she explained, as the head teacher planned to warn children about dangers during the half-term holiday.

They would have been told by the head, Miss Jennings, not to go near the railway line, to be careful of the river and not to go near the colliery.

Yet the biggest danger loomed dangerously on the hillside behind the school.

Mair added that Miss Jennings "could have retired the year before".

Getty Images

Getty Images

Mair Morgan (right) was among a group to take the Princess of Wales around the memorial garden in Aberfan in 2023

The thought takes her to another lost teacher, Michael Davies.

"It was his first teaching job. You could say he'd only worked for a month and a half, which was tragic."

Aberfan remains etched into Welsh history and into Mair's daily life - the former pupils she still sees rarely mention the disaster, she said, but it binds them all.

Mair hopes that - 60 years on - the dangers are not forgotten.

"People must learn lessons from what's happened."

1 hour ago

1

1 hour ago

1