Singapore – Last year, Charlotte Goh received a call from someone claiming to be an officer with Singapore’s Cyber Security Agency.

The caller told Goh that her number was linked to a scam targeting Malaysians and directed her to the “Malaysian Interpol” to file a report.

As a sales professional who often lists her number in public spaces, Goh, who asked to use a pseudonym, found the story plausible.

Over two hours, Goh shared personal details such as her name and identification number, though she hesitated to disclose her exact bank details.

“I wasn’t sure if it was a scam – it sounded so true – but I was also afraid it might be,” she told Al Jazeera.

When she was asked to photograph herself with her official identity card, Goh realised she was being scammed and hung up. Luckily, Goh, 58, was able to quickly change her passwords and transfer funds into her daughter’s account before any money could be stolen.

Others in her circle of friends have not been so fortunate.

“Some friends lost thousands,” she said.

Singapore, one of the world’s wealthiest and internet-savvy countries, has become a prime target for global scammers.

In the 2023 edition of the Global Anti-Scam Alliance’s annual report, Singapore had the highest average loss per victim of all countries surveyed, at $4,031.

In the first half of 2024, reports of scams hit a record high of 26,587, with losses topping $284m.

To combat this, the government has turned to unprecedented measures.

Earlier this month, Singapore’s parliament passed first-of-its-kind legislation granting authorities new powers to freeze the bank accounts of suspected scam victims.

Under the Protection from Scams Bill, designated officers can order banks to block an individual’s transactions if they have reason to believe they intend to transfer funds, withdraw money, or use credit facilities to benefit a scammer.

Those affected still retain access to funds for daily living expenses.

Singaporean police say that convincing victims they are being scammed is a persistent challenge.

Despite numerous anti-scam initiatives, education efforts, and banks’ introduction of features like kill switches, 86 percent of all reported scams in the city-state between January and September 2024 involved the willing transfer of funds.

Common tactics used by scammers include impersonating government officials and creating the illusion of a romantic relationship.

“This Bill allows the police to act decisively and close a gap in our arsenal against scammers,” Minister of State for Home Affairs and Social and Family Development Sun Xueling told parliament.

While the law has been hailed by its supporters as a critical tool to fight rampant scams, it has also stoked debate about the Singaporean government’s famed tendency to intervene in private matters, a model of governance sometimes described as “benevolent paternalism”.

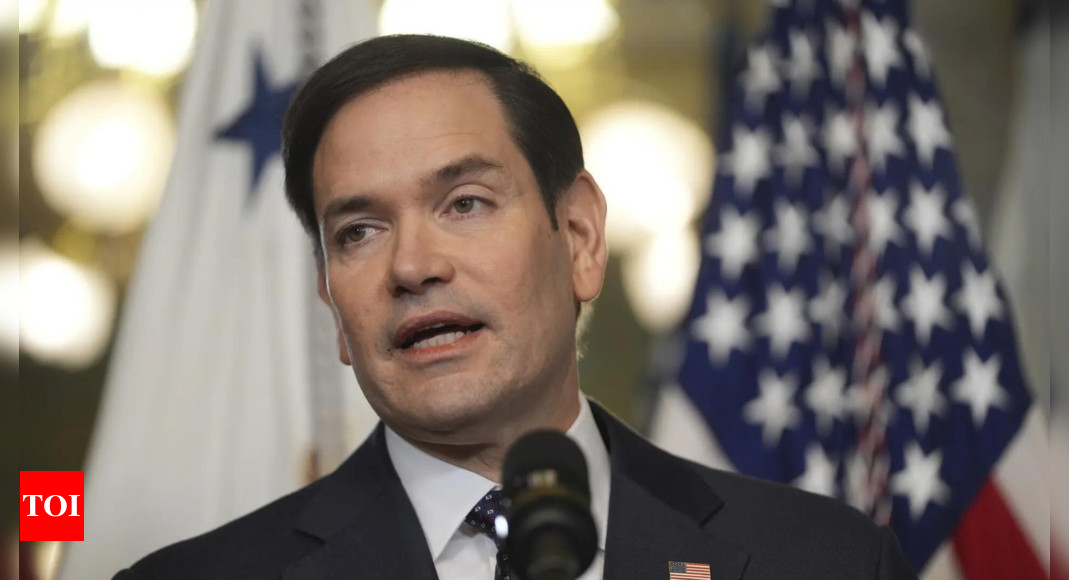

Critics see the law as an extension of the paternalistic governance embodied by Singapore’s founding leader, the late Lee Kuan Yew, who once declared that he was “proud” for the city-state to be known as a nanny state and claimed its economic success was made possible by intervening in personal matters such as “who your neighbour is, how you live, the noise you make, how you spit”.

Singapore’s former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew speaks at the St Petersburg International Economic Forum in St Petersburg, Russia on June 10, 2007 [Alexander Demianchuk/Reuters]

Singapore’s former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew speaks at the St Petersburg International Economic Forum in St Petersburg, Russia on June 10, 2007 [Alexander Demianchuk/Reuters]In his speech to parliament before the bill’s passage, Jamus Lim, an MP with the minor opposition Workers’ Party, expressed concern about the intrusive nature of the law, suggesting individuals be allowed to opt out of its protections or designate trusted family members as administrators of accounts instead.

“One may be uncomfortable specifically with how the bill grants law enforcement an enormous amount of latitude to intervene and restrict what is ultimately a private transaction,” Lim said.

Bertha Henson, a former editor with the Straits Times newspaper, said the legislation was only the latest example of the government intervening in “so many parts of our lives”.

“Can we be adults and not keep running to the State for protection?” Henson said in a Facebook post. “Because we really should think a lot further and ask who is going to protect the individual from the State as well. Or whether we can always be assured that the right hands are on the helm.”

The discussion comes as the government is rolling out a range measures to enhance public security, including plans to double the number of police surveillance cameras to more than 200,000 by the mid-2030s and legal amendments granting police new powers to detain individuals with mental health conditions that are deemed to be a safety risk.

Other recent laws, such as the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act and Manipulation Act and the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Act, reflect efforts to address misinformation and external influence.

While cast as measures to protect national security and social stability, they also grant authorities broad discretionary powers.

Walter Theseira, an associate professor of economics at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS), said the government’s anti-scam legislation reflects the steep economic and social costs of fraud in the city-state.

Theseira noted that many retirees opt to manage significant amounts of money outside Singapore’s mandatory savings scheme used to fund retirement, healthcare and housing needs, putting them “at risk of losing it all”.

“Unfortunately, the right to do what you want with your funds may have to be limited if your decisions end up making you dependent on society or encourage more criminal activity,” Theseira told Al Jazeera.

Eugene Tan, an associate professor at Singapore Management University’s (SMU) School of Law, said the growing losses from scams had spurred a shift towards a “preemptive approach” focused on preventing scams before they occur.

“If not more is done urgently and robustly, then we are not far from an unmitigated disaster,” Tan told Al Jazeera.

“The government is alive to the social cost and it will be remiss in its duties not to deal with the imminent crisis.”

Trust in government

Proponents of the law have argued it is tightly defined in its scope. The legislation specifies that restriction orders will only be issued as a last resort, if all other efforts to convince the individual have failed.

Individuals also have the right to appeal restriction orders, which initially last for 30 days and can be extended up to five times.

While the law could appear intrusive to outsiders, Singaporeans widely expect the government to take an active role in overseeing the welfare and wellbeing of the public, said Tan Ern Ser, an associate professor of sociology at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

“In a sense, Singaporeans want ‘parental support’ but not the ‘control’ aspect of paternalism,” Tan told Al Jazeera, describing the public’s expectation for a “selective, narrower form of paternalism”.

What sets Singapore apart is the public’s high trust in the government, Tan said, citing surveys such as the Asian Barometer and World Values Survey.

Tan pointed out that Singaporeans widely accepted stay-at-home orders, compulsory mask-wearing and contact tracing during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was not “politicised to any significant degree”.

Yip Hon Weng, an MP with the governing People’s Action Party, said that the expanded police powers were a necessary response to the growing problem of scams.

“This ability to act swiftly is a game changer for victims who have been repeatedly targeted, as it prevents further financial losses at critical moments,” Yip told Al Jazeera, sharing the case of an elderly resident in his constituency who had lost his life savings to a scammer posing as a government official.

“Temporarily restricting account access is a drastic step but one that could save individuals from financial ruin. However, such measures must be exercised with care to avoid undermining public trust.”

Yip said the law’s “intrusiveness – temporarily restricting access to accounts – requires a delicate balance” between safeguarding personal agency and robust implementation.

The skyline in Singapore on January 27, 2023 [Caroline Chia/Reuters]

The skyline in Singapore on January 27, 2023 [Caroline Chia/Reuters]While the law is suited to Singapore’s political context, such measures may not be so easily adopted in the global context, some analysts say.

“Countries will have to decide what will work for them and whether there is buy-in for the legislative regime to deal with the scams,” the SMU’s Tan said, suggesting that there is a limit to how much state can intervene, and that “the political cost of such measures cannot be overlooked”.

Already, the law has attracted negative online chatter and cost the government some political capital, said Theseira of SUSS, adding that it “created a talking point that may be used against them in the upcoming elections”.

Singapore’s general elections, which are scheduled to take place by November, come amid growing discontent over housing affordability, rising living costs, income inequality, increasing polarisation and perceived restrictions on dissent in civil society.

The NUS’s Tan said it was unlikely the anti-scam law would set a global precedent in an era of growing distrust in politicians and government.

“All in all, my view is that a high degree of trust in government/institutions, social cohesion and consensus is necessary when an intervention is designed to restrict or restrain for a good, legitimate cause, but with society becoming more fractured and polarised, and entering a post-truth era, ‘fair and foul, and foul is fair’,” Tan said, quoting Macbeth.

4 hours ago

2

4 hours ago

2