Shanaz Musafer

Business reporter, BBC News

Getty Images

Getty Images

Chancellor Rachel Reeves has set out her plans for the UK economy in her Spring Statement and is on track to meet her self-imposed rules on the public finances, which she has said are "non-negotiable".

On the face of it, that sounds like a good thing. So why are people saying that she may struggle to meet them and the only way she may do so is by raising taxes?

It's a complicated picture.

1. Not much spare money

Ahead of the Spring Statement, the chancellor had been under pressure, with speculation over how she would be able to meet her self-imposed financial rules, one of which is to not borrow to fund day-to-day spending.

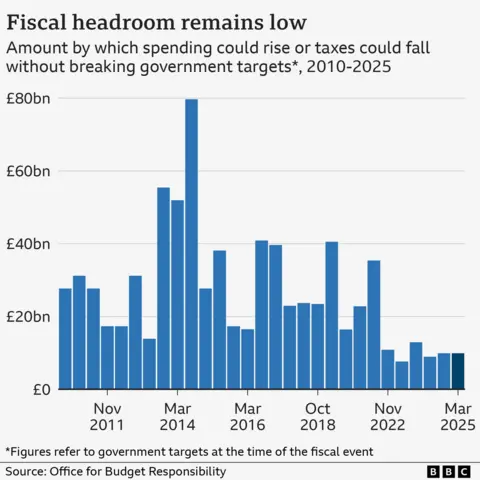

In October, the government's official economic forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), said that Reeves would be able to meet that rule with £9.9bn to spare.

An increase in government borrowing costs since then meant that that room to spare had disappeared. Now big welfare cuts and spending reductions in the Spring Statement have restored it.

Almost £10bn may sound like a lot, but it's a relatively small amount in an economy that spends £1 trillion a year, and raises around the same in tax.

In fact it is the third lowest margin a chancellor has left themselves since 2010. The average headroom over that time is three times bigger at £30bn.

"It is a tiny fraction of the risks to the outlook," Richard Hughes from the OBR told the BBC.

He said there were many factors that could "wipe out" the chancellor's headroom, including an escalating trade war, any small downgrade to growth forecasts or a rise in interest rates.

2. Predicting the future is difficult

Which brings us on to the precarious nature of making economic forecasts.

"All forecasts turn out to be wrong. Weather forecasts also turn out to be wrong," says Hughes.

Predicting what will happen in the future, especially in five years' time is hard, and is subject to revisions. You could be forgiven for not predicting a war or a pandemic, for instance.

The respected think tank, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), has already said there is "a good chance that economic and fiscal forecasts will deteriorate significantly between now and an Autumn Budget".

A case in point, only hours after Reeves delivered her statement in parliament, US President Donald Trump announced new 25% tariffs on cars and car parts coming into the US.

3. Car tariffs a sign worse could come

Reeves admitted the car tariffs would be "bad for the UK" but insisted the government was in "extensive" talks to avoid them being imposed here.

According to the OBR, these import taxes would have a direct effect on goods totalling around 0.2% of GDP.

Before Trump's announcement, the OBR had warned of the risk of an escalating trade war, and while the proposals do not exactly match the watchdog's worst-case scenario, which would see the UK retaliate, Hughes said it had elements of it.

Although 0.2% is a tiny amount, nevertheless it will affect the economy.

And in the OBR's worst-case scenario, 1% would be knocked off ecomic growth.

4. Uncertainty means firms and people don't spend

Trump's trade policies and the fact that nobody seems to know whether he will follow through with his threats, U-turn on them, or how he will react to others is just one way his presidency is making the world so uncertain at the moment.

The war in Ukraine continues, despite Trump's pledge to end it.

The UK, along with Germany, has said it will increase defence spending. Trump has long called for European members of Nato to spend more on defence, and there are also fears that if the US does make a deal with Russia to end the war, that could leave Europe vulnerable.

Domestically, businesses are also facing a worrying time as they brace for a rise in costs in April as employers' National Insurance contributions, the National Living wage and business rates are all set to go up.

Some firms have said they have put off investment decisions as a result, and many have warned of price rises or job cuts. If these materialise, then that will knock growth.

5. Break the rules or raise taxes

Given all of the above, if the chancellor's headroom were to disappear, why would that matter?

Reeves has staked her reputation on meeting her fiscal rules, pledging to bring "iron discipline" and provide stability and reassurance to financial markets, in contrast to former Prime Minister Liz Truss, whose unfunded tax cuts spooked the markets and raised interest rates.

So if she is still to meet her rules and not borrow to fund day-to-day spending, that would mean either more spending cuts or tax rises.

The government has already announced big cuts to the welfare bill as well as plans to cut the civil service and abolish several quangos including NHS England.

But as Paul Dale, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, puts it: "Non-defence spending can only be cut so far."

By leaving herself so little wiggle room and with such a precarious economic outlook, "we can surely now expect six or seven months of speculation about what taxes might or might not be increased in the autumn," says Paul Johnson from the IFS.

That speculation itself can cause economic harm, he says.

Reeves has not ruled out tax rises but told the BBC there were "opportunities" as well as "risks" for the UK economy.

3 days ago

6

3 days ago

6