In March 2023, the Japanese medical authorities announced that the new weight loss drug Wegovy—which was in staggering demand across the world, causing shortages everywhere—had been approved to treat obesity in their country. It sounded, at first glance, like great news for Novo Nordisk, the company that makes Ozempic and Wegovy. But industry outlet the Pharma Letter explained that this would not in fact turn out to be much of a boost. They predicted that these drugs would dominate the market in Japan, but that won’t mean much, for a simple reason: there is almost no obesity there. Some 42% of Americans are obese, compared with just 4.5% of Japanese people. Japan, it seems, is the land that doesn’t need Ozempic.

I wondered how this could be, and if the answer might offer me a way out of a dilemma that was obsessing me. Several months before, I had started taking Ozempic, and I was traveling all over the world to interview the leading experts on these drugs to research my new book, Magic Pill: The Extraordinary Benefits and Disturbing Risks of the New Weight-Loss Drugs. The more I discovered, the more torn I became. I had learned there are massive health benefits to reversing obesity with these drugs: for example, Novo Nordisk ran a trial that found weekly injections reduced the risk of heart attack or stroke by 20% for participants with a BMI over 27 and a history of cardiac events. But I also saw there are significant risks. I interviewed prestigious French scientists who worry the drugs could cause an increase in thyroid cancer, and eating disorders experts who worry it will cause a rise in this problem. Other experts fear it may cause depression or suicidal thoughts. These claims are all fiercely disputed and debated. I felt trapped between two risky choices—ongoing obesity, or drugs with lots of unknowns.

So I went to Japan, to discover: how did they avoid this trap? My first assumption was that the Japanese must have won the genetic lottery—there had to be something in their DNA that makes them stay so slim. But in the late 19th and early 20th century, large numbers of Japanese workers migrated to Hawaii and they have now been living on the island for four generations. They are genetically very similar to the Japanese people who didn’t leave. It turns out that after 100 or so years, Japanese Hawaiians are now almost as overweight as the people they live among. Some 18.1% of them are obese, compared to 24.5% of Hawaiians overall. That means Japanese Hawaiians are four times more likely to be obese than people back in Japan. So something other than genes explains Japan’s slimness. But what?

I glimpsed part of the explanation when I went to the Tokyo College of Sushi & Washoku, to interview the president Masaru Watanabe, who I also spoke with on Zoom on another occasion. He had agreed to cook a meal for me with some of his trainees, and to explain the principles behind it. He told me: “The Japanese cuisine’s [core] feature is simplicity. For us, the simpler, the better.”

He began to make a typical Japanese meal, the kind people were eating all over the country that lunchtime. He and his chefs grilled a mackerel, boiled some rice, made some miso soup, and prepared some pickles. “We don’t traditionally eat meat a lot. We are an island country. We appreciate fish.” As the mackerel was grilled, I watched as various oils and fats leeched out. Even more importantly, Masaru explained, this was an illustration of one of the crucial principles of Japanese cooking. Western cooking, he said, is primarily about “adding.” To make food tasty, you add butter, lemon, herbs, sauces, all sorts of chemicals. “But the Japanese style is totally the opposite.” It’s “a minus cuisine.” It is about drawing out the innate flavor, “not to add anything extra,” he said. The whole point is to try “to make as much as possible of the ingredients’ natural taste.” To Japanese cooks, less is more.

He also said Japanese meals have very small portions, but more of them—five in a typical meal. Before we started to eat, Masaru explained the Japanese principles of eating. The first thing I had to learn was “triangle eating.” All my life, when I was eating a meal with different components, I would mostly eat them sequentially—start the soup, finish the soup; start the salad, finish the salad; start the pasta, finish the pasta. “In Japan, this is regarded as really weird,” he said. “It’s a rude way of eating.” A meal like this should be eaten in a triangle shape. “First, drink the soup a little bit, then go to the side dish—one bite. Then try the rice, for one bite. Then the mackerel—again, a single mouthful. Then go back and have another taste of the soup,” he said. “This is also the key to keep you healthy ... Keeping the balance, so you don’t eat too much.”

The second thing we had to learn is when to stop. In Japan, you are taught from a very early age to only eat until you feel you are 80% full. It takes time for your body to sense you’ve had enough, and if you hit a sense of fullness while you are still eating, then you’ve definitely had too much.

I ate nothing but Japanese food like this on my trip, and three days in, I began to experience an odd mixture of hope and humiliation. I felt healthier and lighter, but I also thought—the Japanese people have built up a totally different relationship to food over thousands of years, in ways we can’t possibly import. So I was surprised to learn that most of Japan’s food culture was invented very recently—in living memory, in fact. Barak Kushner, who is professor of East Asian History at the University of Cambridge, told the writer Bee Wilson, for her book First Bite, that until the 1920s, Japanese cooking was just “not very good.” Fresh fish was eaten only once a week, the diet was dangerously low in protein, and stewing or stir-frying were not much of a thing. Life expectancy was a mere 43. It was only when Imperial Japan was creating an army to attack other parts of Asia that a new food culture began to be invented, quite consciously, to produce healthier soldiers. After the defeat of Japan in the Second World War, when the country was in ruins, the new democratic government stepped up this transformation.

To find out how Japan created a radically different food culture, I arrived at Koenji Gakuen School with my translator on a stiflingly hot September morning. It’s a typical school for kids aged from five to 18 in a middle-class neighborhood in Tokyo. We were greeted near the entrance by Harumi Tatebe, a woman in her early 50s, who had been the nutritionist there for three years. As we walked through the corridors, kids waved at her affectionately, and shouted her name, eager to know what they were having for lunch that day. By law, Harumi said, every Japanese school has to employ a professional like her. It took her three years to qualify, on top of her teaching degree, and she explained that in this position, you have several important roles to play. You design the school meals, in line with strict rules stipulating that they must be fresh and healthy. You oversee the cooking of the meals. You then use these meals to educate the children about nutrition. Then you educate their parents on the same topic.

Children eat lunch at a nursery school in Yokohama, Japan.

Kazuhiro Nogi—AFP/Getty Images

Children eat lunch at a nursery school in Yokohama, Japan.

Kazuhiro Nogi—AFP/Getty ImagesHarumi told me that today’s meal consisted of five small portions: some white fish, a bowl of noodles with vegetables, milk, some sticky white rice, and a tiny dollop of sweet paste. All the kids eat the same meal, and packed lunches are forbidden. No processed or frozen food ever goes into any of the meals here. “We start from scratch,” she said. “It’s all about nutrition ... Sometimes with frozen food, they use a lot of artificial additives.”

Once the meal was ready, Harumi carried a tray over to the office of the school’s head, Minoru Tanaka. It is a legal requirement that the principal of each school ensures lunches meet nutritional guidelines. It’s also customary for principals to have the same lunch as the kids and to eat it first, to make sure it’s safe, nutritious, and delicious. He rolled up his sleeves and dug in. After a moment, he nodded approvingly. Before they began to eat, a child stood at the front of the class and read out what today’s meal was, which part of Japan it came from, and how the different elements are good for your health. She then said “Meshiagare!,” the Japanese equivalent of “bon appétit,” and everyone applauded.

While the kids were eating, Harumi held up some colored ropes. Each one represented a different kind of food you need to be healthy. On this day, she held up the yellow rope, representing carbs, and asked what they do for your health. A child yelled: “Give you energy!” She held up the red rope, representing calcium, and a child yelled that it makes your bones stronger. As she went though the food groups, she tied each rope together, to show that in combination they make a healthy meal. “Through the school lunches, we explain the food itself,” the principal, Mr. Tanaka, told me.

As I walked around, I had a nagging sense that there was something unusual about this place. But it was only after a few hours that I realized what it was. There were no overweight children. None. My translator and I walked from class to class, asking the kids what they most liked to eat. The first child I spoke to, a 10-year old girl, said: “I like green vegetables, like broccoli.” One 11-year old-boy told me he loves rice because “the rice has protein. If you eat balanced food every meal, then you have a very strong body,” and he flexed his tiny biceps, and giggled.

I asked my translator: Is this a joke? Are they trolling me? A bunch of 10-year-olds, telling me how much they love broccoli and rice? But most of the Japanese people I discussed this with were puzzled to see that I was puzzled. We teach kids to enjoy healthy food, they explained. Don’t you?

Up until this point, I had seen aspects of Japan’s approach toward health that seemed totally admirable. But next, I saw something that left me with mixed feelings. In 2008, the Japanese government noticed that obesity was slightly rising. So they introduced the “Metabo Law,” which was designed to reduce the negative consequences of a large waistline. The law contained a simple rule. Once a year, every workplace and local government in Japan has to bring in a team of nurses and doctors to measure the waistline of adults between ages 40 and 74. If the measurements are above a certain level, the person is referred to counseling, and workplaces draw up health plans with employees to lose weight. Companies with fattening work forces can face fines.

I couldn’t imagine how this could possibly work, so I went to see it in practice. A company called Tanita agreed to let me talk to their employees about it, and to see the measures they have put in place. They make vegan food, healthy meal replacements, and exercise equipment, so they are especially keen to promote a healthy Japan. Different companies stay in line with the Metabo Law in different ways, and Tanita is at the most enthusiastic edge.

The first person I met with was Junya Nagasawa, the company’s boss. He is a handsome 57-year-old who consistently comes top of the company’s walking league table, with nearly 20,000 steps a day. When the Metabo Law came into force, he told me, there was a sudden demand from companies for technologies that could help them monitor their employee’s health and find ways to improve it, so Tanita designed video screens and health surveillance systems. Everyone in the company wears a watch that tracks how many steps they walk a day, and when you arrive at work every day, it tells you how much you’ve walked—and how much your colleagues have walked. You are encouraged to post photos of all your meals, and pledges for how you’ll improve your health—which are, again, visible to the entire company.

Nagasawa told me these measures meant he started to walk much more. “It’s not difficult to walk, but it’s very difficult to make the time,” he said. Now, he gets up earlier, and gets off the subway four stops sooner to walk the rest of the way. “I had to be the role model,” he said.

I spoke with some of his employees. The 33-year-old Yusuke Nagira told me he came to work here straight from university, and he had never done anything to look after his health up to that point. “I would eat whatever I wanted to eat and didn’t exercise at all. That was my lifestyle.” But he noticed from logging his weight that he was putting on pounds, and he was conscious of the looming annual health checks. So he made some changes. Before, “when I was watching TV, I would usually eat junk food or snacks.” He cut them out completely. And “when I go out to other places, I try not to use trains or drive, but walk.” Knowing he’ll be accountable helps him, he said. I heard this again and again from the workers.

I told all the Japanese people I talked to that if you tried this in the U.S. or Britain, people would be outraged and burn down their offices. They invariably looked puzzled, and asked me why. I said that people would feel like it was not their employer’s business what they weighed, and that it was a monstrous intrusion of their privacy. Most of them nodded politely, said nothing, and looked at me like I was slightly crazy. Nagira said simply: “Being fat is not good.” I felt like I was communicating across a cultural chasm. Whatever you think of its ethics, the Metabo Law does seem to be—along with Japan’s other measures—having an impact. Its obesity rate is currently the lowest level in the rich world.

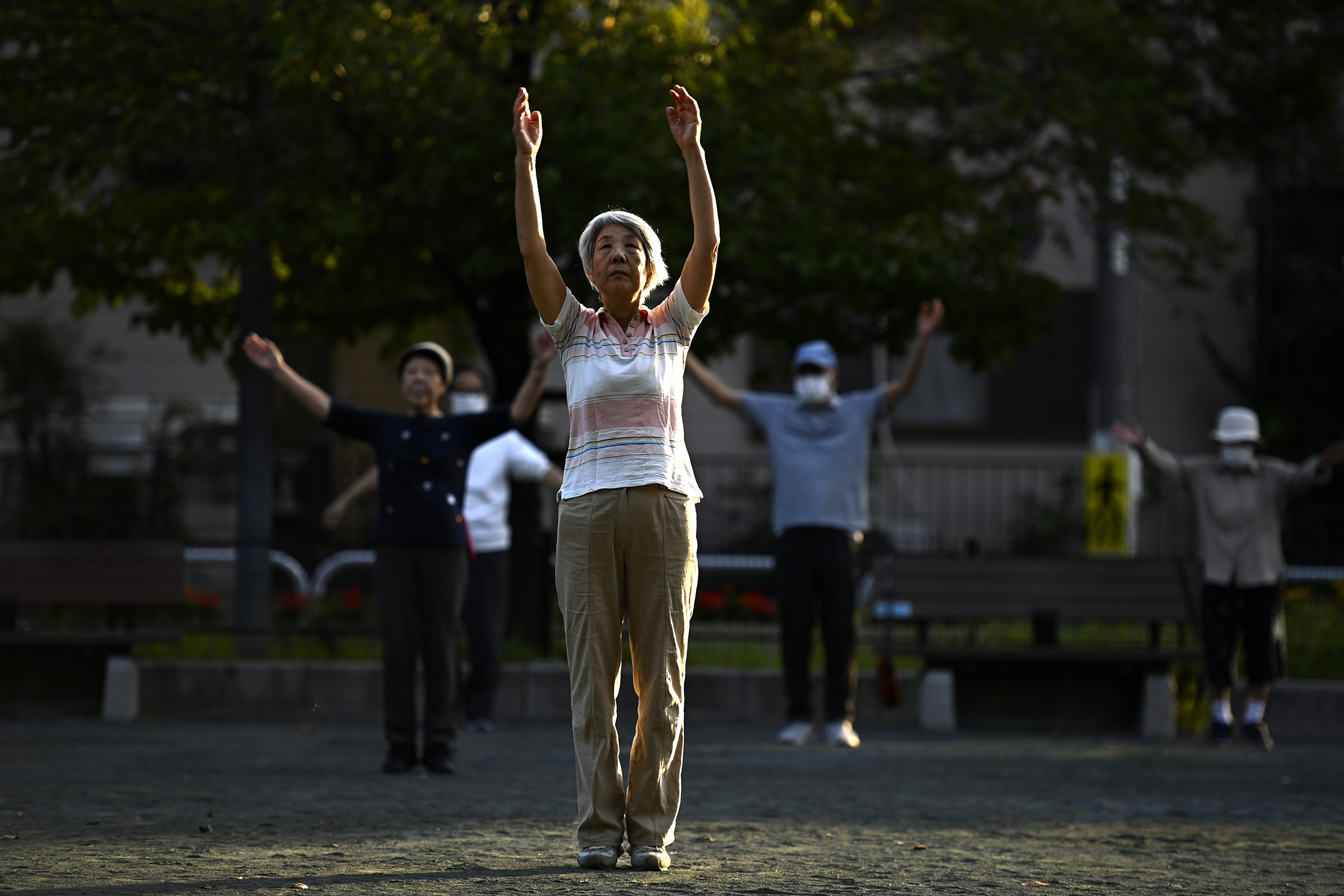

As I traveled across the country, I began to see what you gain if you live in the Japanese style. Every morning around 7 or 8 a.m., in parks across Japan, elderly people gather in groups and exercise together. You can watch people in their 80s and 90s dancing or doing yoga. Japanese people live longer than anyone else on earth. On average, men live to be 81, and women reach 88. Even more importantly, they remain healthy for longer.

A group of elderly people exercise early in the morning in a park in Tokyo on Oct. 1, 2022.David Mareuil—Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

A group of elderly people exercise early in the morning in a park in Tokyo on Oct. 1, 2022.David Mareuil—Anadolu Agency/Getty ImagesI went to Okinawa, an archipelago of islands in the far south of the country, to track down somewhere that sounds almost mythical—a place that is described by local Japanese authorities as the village with the oldest population in the world (though another village in Japan has recently been declared the oldest in the country). By the side of a lush tree-covered mountain, we drove into Ogimi. It has 215 households, and 173 people there are aged 90 or older. The people who live here have had hard lives—they were mostly poor farmers, and during the Second World War, in the space of just three months, roughly a third of the population was killed during the Battle of Okinawa.

In their little concrete community center, some of the very elderly residents were arriving, looking forward to catching up with each other, playing games and exercising together. The first person we met was Matsu Fukuchi, a 102-year-old woman, who had walked to the center from her home, slowly but without a stoop, holding on to a cane. Her eyes watched us with curiosity. She said she took a lot of pleasure in life. “I get together with my grandchildren and have fun, and dance. I love to dance.”

Some traditional Okinawan music began to play, and Matsu put on a brightly colored kimono. Then slowly, carefully, joyfully, she stood up, and began to dance. She moved her hips gently in time with the music, and the other women matched her rhythm, waving their arms. She looked toward me, beaming.

As I watched these centenarian women move with the music, I realized—this is what this whole journey has been about. While she waved her 102-year-old hips in my direction, I thought: This is the potential prize here, if we can solve the obesity crisis. More life. More health. More years of joy.

Suddenly, the sheer artificiality of the obesity crisis seemed clear to me, more than at any other point on this journey. It is created by the way we live. It should be possible, therefore, to un-create it. But how can we do that? At first glance, the gap between us and the Japanese seemed unbridgeable. But then I thought about something from my own childhood. If I could take a young person back to the Britain or the U.S. of the 1980s, they would be astonished by one habit. People smoked cigarettes everywhere. They smoked in restaurants. They smoked on planes. They smoked on game shows. When you went to see the doctor, he would smoke while he examined you. (I’m not kidding: I remember this happening.) If you had said to people then that within a generation, smoking would come to look like a thing of the past, we would not have believed you. In 1982, for example, 33% of men and women in the Minnesota Heart Survey were smokers. Today, only 12% of the U.S. population smokes cigarettes, and it’s falling further.

I had asked Masaru Watanabe, the Japanese chef, if it was possible for Westerners to become like the Japanese. “I hope so,” he said. “I definitely think so,” he clarified. I have traveled to many different parts of the world where they have begun changes that bring us closer to Japanese levels of health. In Mexico, they introduced a sugary-drinks tax. In Amsterdam, they restricted sugary drinks from schools and gave overweight kids personalized health coaches, slashing childhood obesity by 12% between 2012 and 2018 (though it has ticked up since). In various U.S. cities, there are “food is medicine” programs. There are dozens of social changes we could make that would reduce the huge forces driving up obesity.

None of this, in the short term, can get me out of the dilemmas posed right now by the new weight loss drugs. In the U.S. and other rich countries (with the exception of Japan), many of us will have to weigh the risks of continuing to be overweight, against the risks of taking these drugs. I am continuing to take Wegovy, but with a heavy sense of concern about the potential dangers. Yet Japan shows us that if we make the right social changes now, we can free our children of this dilemma. If we look East, we will realize we don’t have to be trapped in the choice between Wegovy versus weight gain forever.

Adapted from MAGIC PILL: The Extraordinary Benefits and Disturbing Risks of the New Weight-Loss Drugs by Johann Hari. Copyright © 2024 by Johann Hari. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

8 months ago

41

8 months ago

41