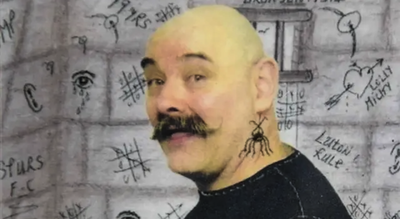

Charles Bronson has spent more than 50 years in prison (Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

After more than half a century behind bars, Charles Bronson, born Michael Gordon Peterson and now legally known as Charles Salvador, and famously portrayed by Tom Hardy in the 2008 film Bronson, is once again at the centre of a parole review.Now 73, he is widely regarded as Britain’s most notorious prisoner and was due to have his case considered on 18 February. In the weeks leading up to the review, he dramatically sacked his legal team and refused to take part after being told his request for a public hearing had been rejected. In a letter to Sky News, he wrote: “Sacked the legal team!” and said he wanted nothing to do with what he called the “farcical jam roll,” his term for parole, asking: “What are they afraid of? The truth getting out?” A new solicitor has since been appointed and secured a postponement.

The Parole Board is now conducting a paper review rather than holding a fresh oral hearing. The panel will examine written statements from prison staff, probation officers, psychiatrists and Bronson’s legal representatives before deciding whether he can be safely released, transferred to an open prison, or whether the case should proceed to a further oral hearing. No decision has yet been publicly confirmed. What is clear is that this is his ninth attempt at parole.

What the Parole Board is weighing

This latest review is not a public spectacle. It is an administrative exercise focused on risk. The panel’s task is straightforward in principle: does Bronson pose a risk to the public, and if so, can that risk be managed through licence conditions and restrictions? If the risk is deemed too high, he remains where he is. At his last full parole hearing in 2023, one of the first public parole hearings in England and Wales, secured after Bronson successfully challenged the secrecy of the process, the board accepted that his behaviour had improved.

However, it concluded he was not ready for transfer to an open prison. It recommended that he be tested in a less restrictive regime as a step towards potential release.

Bronson pictured in 1997/ SkyNews

That progression does not appear to have materialised. Bronson remains in a high-security prison, segregated and locked in his cell for around 23 hours a day. Decisions about reducing his security classification lie with the Ministry of Justice, which does not comment on individual cases. Bob Johnson, a psychiatrist who worked with Bronson three decades ago, has publicly argued that he is being “unjustifiably punished,” describing the length and intensity of his solitary confinement as “unbelievable.” Johnson believes Bronson is heavily institutionalised but could cope outside with structured support and income from his artwork. The Parole Board, however, must weigh that optimism against a long record of violence.

Five decades behind bars: how a seven-year sentence became a life term

Bronson was first jailed in 1974 at the age of 22 for armed robbery. The original sentence was seven years. With the exception of two brief periods of release, 1987 and 1992, he has remained in custody ever since. While serving his initial term, he was convicted repeatedly for violent assaults on prison staff and inmates in 1975, 1978 and 1985. He was released in 1987 at 34, but after just 69 days was returned to prison for robbing a jeweller.

In 1992 he was freed again, only to be jailed weeks later for intent to rob.

Bronson has spent more than 50 years behind bars/ SkyNews

The most consequential episode came in 1999 at Hull prison, where he held a prison art teacher hostage for around 44 hours. The teacher was not physically injured but was left traumatised and did not return to work. Bronson received a discretionary life sentence with a minimum tariff of three to four years, which expired in the early 2000s. He has remained detained ever since because the Parole Board has repeatedly judged him too risky to release. His last conviction was in 2014 for assaulting a prison governor, resulting in a further three-year sentence. Across the decades, Bronson has taken hostages including a deputy governor, staff and inmates, staged protests, and engaged in repeated violent outbursts. He has been moved between numerous high-security prisons and secure hospitals, including Broadmoor, Rampton and Ashworth. In the late 1970s and early 1980s he was transferred to psychiatric hospitals after assaults and suicide attempts, and at one stage attempted to strangle fellow patient

John White

. Former Belmarsh governor John Podmore has said he once placed Bronson in a normal cell and worked to curb his behaviour. The arrangement lasted only weeks.

Reinvention, art and public mythology

Outside prison, Bronson briefly fought in illegal bare-knuckle boxing contests and adopted the name Charles Bronson after the Hollywood actor. Over the years he has also used names including Charles Ali Ahmed, following a short-lived conversion to Islam, and, more recently, Charles Salvador. His notoriety has been amplified by popular culture. The 2008 film Bronson, directed by

Nicolas Winding Refn

and starring Tom Hardy, dramatised his life and cemented his public image as a theatrical, volatile anti-hero.

Inside prison, Bronson has channelled much of his energy into art and writing. Since 1999 he has had 11 books published, including Respect and Reputation and Loonyology: In My Own Words. In February 2023, hundreds of his drawings were exhibited and offered for sale, with prices ranging from £700 to £30,000.

The works are vivid, often depicting confinement, madness and despair, but occasionally carry handwritten messages of hope, including: “God save our dreams. It’s all we have left. One simple dream will bring you through all this misery.”

Supporters argue that his art demonstrates transformation. Critics see performance layered over a record of violence.

Marriages, religion and private life behind bars

Bronson’s personal life has unfolded largely within prison walls. He married Irene Kelsey in 1971; and eight months later, the couple wed and had their first son named Michael Jonathan Peterson. In 2001, he married Fatema Saira Rehman at HMP Woodhill after she began writing to him. He briefly converted to Islam and took the name Charles Ali Ahmed. The marriage ended four years later, and he renounced both Islam and the name. In 2017 he married Paula Williamson, a former Coronation Street actress, after she began visiting him in prison. The marriage was annulled in 2018.

Williamson was found dead at her home in 2019; police said her death was not suspicious. Bronson has spoken publicly about wanting to be released to fulfil what he described at his 2023 hearing as his mother’s “last dream.” At that hearing he admitted that in earlier years he “couldn’t stop taking hostages,” describing it as “battling against the system.” He told the panel he was “almost an angel now” compared with his younger self.

Is he likely to be released?

Bronson has now spent approximately 52 years in custody, one of the longest periods served by any British prisoner. Much of that time has been in solitary confinement. For release to occur, the Parole Board must be satisfied that the risk he presents can be safely managed in the community. Alternatively, it could recommend a move to an open prison as an intermediate step. It could also decide that further testing or a fresh oral hearing is required.

Bronson remains hopeful that he will one day be released/ Image: PA

The central question has not changed in decades: is Charles Bronson a man who has aged out of violence, or one whose history makes him too unpredictable to trust? At 73, he remains hopeful. In his recent letter, he referenced a “freedom party” planned for 2028, telling readers: “Don’t be late.” Whether that party ever takes place depends not on reputation, art or mythology, but on a risk assessment now unfolding quietly on paper.

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1